A Dynamic Approach to Project Euler

Background

On the rare occasion that I’ve got a spare moment - and there is no project I’m actively procrastinating on finishing - I’ll try my hand at knocking out some of the challenges offered by Project Euler.

To those unfamiliar with the site, Project Euler is a selection of mathematic and programming challenges that often require a special combination of mathematical insight and clever programming to solve. According to the site, “The motivation for starting Project Euler, and its continuation, is to provide a platform for the inquiring mind to delve into unfamiliar areas and learn new concepts in a fun and recreational context.”

Basically, its a nerdy website for other nerds to nerd out on fun problems, for nothing but the glory of knowing “I solved this”. For me, its almost the perfect nerd snipe

As of this posting, the site features a total of 796 problems, and the difficulty of these problems scales roughly with the problem number. I found myself inspired to write a quick blog about a solution to a few of these exercises, since several solutions involved an old friend that I haven’t seen since my college algorithms class: dynamic programming.

Since I am operating more in the computer security space these days, and less so in the software development and computer science space, dynamic programming is a concept that I rarely encounter in my day-to-day work. It should never be too far out of mind though, as its a really powerful tool when wielded with authority.

What is Dynamic Programming

If you’ve ever taken a course on algorithms, right now your eye is likely twitching with the recollection of painful nights spent over problemsets trying to find the best way to slice a rod, the optimal packing of objects in a knapsack, or the most efficient way the drop the class while still maintaining a half-decent GPA.

But today we visit our old friend - dynamic programming - under much friendlier circumstances and a lot lower stakes.

There are two key attributes that a problem must have in order for dynamic programming to be applicable:

-

optimal substructure: the most optimal solution for input \(n\) can leverage the optimal solution for previous cases or sub-problems. In other words, the solutions for \(k < n\) can be used to provide a solution for \(n\).

-

overlapping sub-problems: the problem can be broken down into sub-problems which are reused several times. Often times you can exploit the naturally recursive structure of these sub-problems to create an algorithm that solves the same sub-problem over and over rather than needing to compute new sub-problems as they arise.

If your problem meets these two criterion, then congratulations! Its a perfect candidate for a dynamic programming approach to tackling the solution.

If a problem can be solved by combining optimal solutions to non-overlapping sub-problems, the strategy is called “divide and conquer” instead. This is the main reason why other popular algorithms with a naturally recursive nature, such as merge sort and quick sort, are not technically considered examples of dynamic programming - despite that both their methods reconstruct the sorted list from previously sorted sub-lists.

Phew, thats enough theory… for now. Let’s start tackling the problems!

Exercise 20: Find the sum of the digits in the number 100!

To clarify, that exclamation point is a factorial. We aren’t just strangely excited to tackle this problem. Calculating a large factorial is a classic scenario where dynamic programming is an applicable strategy, since the factorial operation is “naturally recursive”.

However, if we naively try to use function-based recursion to implement the solution we may find ourselves in a world of pain. To demonstrate, lets come up with a recursive solution Which we can later compare with our dynamic programming-based solution.

Factorial(n): function call recursion

# Q: Find the sum of the digits in the number 100!

# A: Use recursion + function call stack to lazily calculate n!

def find_factorial(n):

if n == 0 or n ==1 :

return 1

else:

return n*find_factorial(n-1)

# get target number (100!)

target_num = find_factorial(100)

# print sum of digits in target_num

print(sum([int(i) for i in str(target_num)]))

Fortunately, the recursion depth in python didn’t cut us off for our target input \(n=100\), but this solution won’t scale effectively for arbitrary \(n\).

Instead, lets use fact that \(n! = n*(n-1)*...*1 = n*(n-1)!\) to our advantage. Instead of using naive function-based recursion, what if we kept track of the previous values of \(k!\) for \(k < n\) and used those values to calculate \(n!\).

Essentially, we are making a classic time vs space complexity tradeoff, where we can be guaranteed \(O(1)\) time to access \(k!\), where \((k < n)\), all for the small price of an array of size \(n\).

First, we’ll declare a large enough array to store our \(k!\) values. We can also use the fact that items in an array have a natural index to them to keep a sane storage scheme, so that the \(k\)-th array index stores the value of \(k!\).

From here, the algorithm is a simple tweak to our naive solution. We’ll still be using a form of recursion here, but instead of relying on the recursion inherent in the function call stack, we’ll have everything we need stored in our array.

All we need to do is check if the \(k\)-th index is nonzero. If it is, then we’ve already calculated that value previously and can just return the current value of \(array[k]\). If we encounter a zero, we know this is a new value for the array, so we should populate the current array index before returning. Lastly, we need to check for the terminal case of \(n=1\) or \(n=0\), since this would mean we’ve hit recursive bedrock. Below we have outlined the complete algorithm.

Factorial(n): dynamic programming

# Q: Find the sum of the digits in the number 100!

# A: keep track of previous factorial in array

# dont need more than 100 spaces in array

# we will store factorial(n) at slot n in the array

factorials = [0]*101

def find_factorial(n):

if n == 0 or n ==1 :

return 1

else:

if factorials[n] != 0:

return factorials[n]

else:

factorials[n] = (n * find_factorial(n-1))

return factorials[n]

# get target number (100!)

target_num = find_factorial(100)

# print sum of digits in target_num

print(sum([int(i) for i in str(target_num)]))

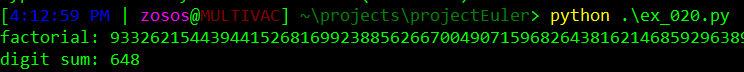

Now, lets verify the output was correct. The original problem called for calculating the sum of the digits in \(100!\). As seen in our partially truncated screenshot below, our new algorithm gives us the correct answer of \(648\).

Exercise 25: What is the index of the first term in the Fibonacci sequence to contain 1000 digits?

The Fibonacci sequence is another classic example where dynamic programming seems to be a natural candidate for developing a solution, as the sequence itself is defined by a recursive structure. Since the value of the \(n\)-th Fibonacci number only depends on the \((n-1)\) and \((n-2)\) Fibonacci numbers, we can use a trick similar to the one in problem #20 to keep track of Fibonacci values as we go!

Fibonacci(n): dynamic programming

# Q: What is the index of the first term in the Fibonacci sequence to contain 1000 digits?

def count_digits(n):

return len(str(n))

#off by 1 error depending on if you start the sequence at f0 or f1

#dynamic programming using tabulation to calculate fib w/o recursion

def find_fibonacci_digit(n):

Fibonacci_numbers = [0,1,1]

digit_count = 0

i = 3

while digit_count < n:

next_term = Fibonacci_numbers[i-1] + Fibonacci_numbers[i-2]

digit_count = count_digits(next_term)

Fibonacci_numbers.append(next_term)

i+=1

return i

# print index of Fibonacci number with over 1000 digits

print(find_fibonacci_digit(1000))

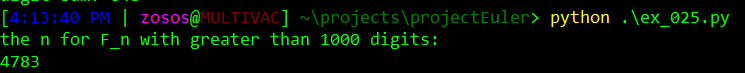

Again, by storing the value of the current Fibonacci number in an ever-growing array, we’re using a classic time vs space tradeoff to boost our performance and keep from blowing up the function call stack. Once again, we receive the correct answer of \(4783\).

However, Project Euler problems often times have sneaky solutions whose discovery depends on clever mathematical insights, instead of relying on sound computer science.

For example: Did you know there is actually a closed-form formula for finding the \(n\)th Fibonacci number, without using recursion?

Fibonacci(n): Proving a closed form formula

Although our fancy-pants dynamic programming allowed us to find a relatively efficient solution without too much trouble, it turns out there’s a clever, closed-form way to get the exact \(n\)th Fibonacci number!

To demonstrate how to derive this formula, first recall the classic recursive definition of the Fibonacci sequence:

\[\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} F_{n} &= F_{n-1} + F_{n-2} \end{aligned}\end{equation}\]If we were to enumerate the elements of the sequence, it would look something like

\[(1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21...)\]But in order for us to “kick off” this sequence, we always have to define our initial values \(F_0\) and \(F_1\) for the recursive definition to hold. If we define \(F_0,F_1 = 1\) then we can recover the “classic” Fibonacci sequence shown above. However, we could also let \(F_0=0, F_1=1\) and then we would have:

\[(0,1,1,2,3,5,8,13...)\]So which of these is the real Fibonacci sequence? Well, that’s a trick question. They both are the Fibonacci sequence, with different initial conditions. In other words, there’s a more “essential” structure at play here: a linear recurrence relation

Recalling a basic fact from linear algebra, we note that the set of (possibly infinite) integer sequences is a vector space. This motivates us to use an approach from linear algebra to derive our closed form formula.

Consider the initial conditions for a Fibonacci sequence as the 2d vector

\[\begin{bmatrix} F_{1} \\ F_{0} \end{bmatrix} = \vec{x_{0}}\]We can now express our Fibonacci problem as a matrix difference equation. To be more explicit with our notation, we are seeking the \(A \in M_n(\mathbb{C})\) such that

\[\begin{bmatrix} F_{2} \\ F_{1} \end{bmatrix} = A \vec{x_{0}}\]A bit of algebra reveals to us that

\[A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Thus, I claim (by induction) that, for \(n \in \mathbb{N}\):

\[\begin{bmatrix} F_{n+1} \\ F_{n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} F_{n} \\ F_{n-1} \end{bmatrix}\]The base case was already proven above (hint: just do the multiplication), so we just need to cover the inductive step. To demonstrate briefly, if we do the multiplication above, we see that:

\[\begin{bmatrix} F_{n} + F_{n-1} \\ F_{n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} F_{n+1} \\ F_{n} \end{bmatrix} \implies \vec{x}_{n+1} = A\vec{x_{n}}\]What we’ve just shown is that \(A\) is the characteristic matrix for this difference equation. Now we proceed to find the characteristic equation for this matrix:

\[\begin{aligned} det(A-\lambda I) &= (\lambda -1)(-\lambda) - 1 \\ &= \lambda^2 - \lambda -1 \\ \end{aligned}\]Solving for the roots of this polynomial gives us the eigenvalues \(\lambda_{1,2}\):

\[\begin{aligned} 0 &= (\lambda - \phi) (\lambda + \phi^{-1}) \\ \phi &= \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} = \lambda_{1} \\ -\phi^{-1} & = \frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2} = \lambda_{2} \end{aligned}\]Here we are using the convention of \(\phi\),\(-\phi^{-1}\) to denote the golden ratio and it’s conjugate, respectively. One of my favorite fun facts about math is how you can recover the golden ratio via the Fibonacci sequence, which is what we’ve stumbled on here.

We continue by finding the eigenvalues \(v_{1,2}\) corresponding to each eigenvector:

\[\begin{aligned} v_1 &= \left( \begin{array}{c} \phi \\ 1 \end{array} \right) , &v_2 = \left( \begin{array}{c} -\phi^{-1} \\ 1 \end{array} \right) \end{aligned}\]We can use these eigenvectors to obtain a diagonalization of \(A = SDS^{-1}\), where

\[\begin{aligned} A &= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \\ \end{bmatrix} , &D = \begin{bmatrix} \phi & 0 \\ 0 & -\phi^{-1} \\ \end{bmatrix} \\ S &= \begin{bmatrix} \phi & -\phi^{-1} \\ 1 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} , &S^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -\phi^{-1} \\ -1 & \phi \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]Recall a fact from algebra, that for any diagonalizable matrix \(A^n = SD^nS^{-1}\). Also, consider that

\[\vec{x}_{n+1} = A\vec{x}_{n} \implies \vec{x}_{n+1} = A^{n}\vec{x}_{0}\]This implication is immediately clear if we expand out the expression to its base case \(\vec{x_{0}}\):

\[\begin{aligned} \vec{x}_{n+1} &= A\vec{x}_{n} = A(A\vec{x}_{n-1}) = A^2\vec{x}_{n-1} \\ &\dots \\ &= A^n\vec{x_{0}} \end{aligned}\]Putting this all together, we get

\[\begin{aligned} \vec{x}_{n+1} &= A^n\vec{x_{0}} \\ &= S D^n S^{-1}\vec{x_{0}} \\ \end{aligned}\]I’ll leave this last bit here as an exercise to the reader (hint: just do the matrix multiplication and check the entries of the resulting vector). I think its actually a rather fun bit of algebra to do for yourself. Either way, we end up with the following closed-form formula!

\[\begin{aligned} F_n &= \frac{\phi^n - (-\phi^{-n})}{\sqrt{5}} \\ & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}} \left( \matrix{\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}} \right)^n - \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}} \left( \matrix{\frac{1-\sqrt{5}}{2}} \right)^{n} \end{aligned}\]Below is some script code that uses the formula we derived to implement a solution to problem 25. We are using the mpmath library for arbitrary precision when calculating the square roots and additional computation-heavy operations. If we merely relied on Pythons native types and math library functions, our results would be incorrect due to truncation and imprecision when calculating large \(n\).

def find_fibonacci_exact(n):

phi = (1+sqrt(5))/2

phi_inv = (1-sqrt(5))/2

dc= 0

i = 100

while dc< n:

fn = int((power(phi,i) - power(phi_inv,i))/sqrt(5))

dc = count_digits(fn)

i+=1

return i

Time Trials

To prove I’m not just pedantically flexing algorithms knowledge for no reason, I’ve come up with a small snippet of code to time each of the solutions presented in this post. If we’ve done our homework correctly, we should see fairly drastic performance improvements between the dynamic programming vs naive recursive solution.

I used the timeit library in python for these quick performance tests (but I should really be using a more system-level language… you’ll see what I mean here shortly).

Ex 20 Timing

Here’s the timer I used for the comparison of the factorial solutions.

if __name__ == '__main__':

import timeit

mysetup = '''from __main__ import find_fibonacci_exact

from mpmath import sqrt,power'''

print(timeit.timeit("find_factorial(100)", setup="from __main__ import find_factorial", number=1000))

print(timeit.timeit("find_factorial_dynamic(100)", setup="from __main__ import find_factorial_dynamic", number=1000))

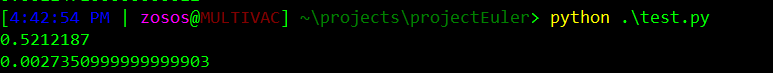

Below are the results! Unsurprisingly, our dynamic programming solution was several orders of magnitude faster than naive recursion.

Ex 25 Timing

Here’s the timer I used for the comparison of the Fibonacci solutions, it was continued from the __main__ method above.

print(timeit.timeit("find_fibonacci_digit(100)", setup="from __main__ import find_fibonacci_digit", number=1000))

print(timeit.timeit("find_fibonacci_exact(100)", setup=mysetup, number=1000))

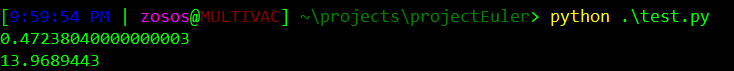

And once again the results… although this time they are a bit unexpected. Our “exact calculation” solution is way slower than our dynamic programming version.

We might expect to see the direct computation outperform our dynamic programming variant, but in reality that assumption isn’t always true. Our performance issues are attributable to a few factors:

- We rather stupidly directly calculate \(F_n\) every time, and then check the digit length. Compare this with the dynamic programming solution which “pre-computed” and stored solutions for later

- We required the additional overhead of the

mpmathlibrary to ensure truncation didn’t lead to errors, instead of trusting Python’s native types - Potentially hidden optimizations/loop unrolling occurring at a lower system context than the Python interpreter

Seems like our choice of using Python to tackle these exercises can lead us astray at times - the more you know!

Final Thoughts

If you’re curious about some of my other solutions to these exercises, I’ve published a small selection of these to my github. Please note that Project Euler kindly requests that nobody post solutions to exercises past number 100, in order to keep the competition fair and fun for everyone.

Especially since the difficulty really ramps up in the later challenges, and solving any of these is an accomplishment onto itself. In that same spirit, I’m only planning on publishing my solutions up to exercise 25 (for now). Thanks for reading!

Sources

- Project Euler

- nerd snipe

- Dynamic Programming (Wikipedia)

- Merge sort (Wikipedia)

- Quick sort (Wikipedia)

- Space–time tradeoff (Wikipedia)

- Recurrence relation (Wikipedia)

- Sequence space (Wikipedia)

- Matrix difference equation (Wikipedia)

- Characteristic polynomial (Wikipedia)

- Golden ratio (Wikipedia)

- Diagonalizable matrix (Wikipedia)

- Diagonalizable matrix - Application to matrix functions (Wikipedia)

- mpmath

- timeit module (Python Docs)